Blogbook -- Racist Hegemony And the Language Choices We Make

Entry 17

Vico’s common sense and Marxism’s dialectic help us understand racist discourse as a dialectic that is both language and logos and material practices and decisions, all of which are accomplished in the world around us. These two aspects of racist discourse reinforce each other. Being a mutually reinforcing dialectic means that racist discourse is racist common sense, which also means racism is systemic, or structural in our world, work, and lives.

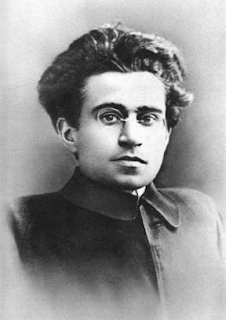

To really take advantage of what Marxian theory offers, we shouldn’t stop with classical Marxism. Theorists such as Antonio Gramsci, reconsidered the classical Marxist dialectic. He explained that actually both the base and superstructure operate simultaneously, influencing each other. You cannot consider one before the other, as classical Marxism did -- that is, everything sprang out of the material base. So for Gramsci and others the dialectic of base (material conditions and outcomes) and superstructure (language about and reflection on one’s world) mediate one another (note 103).The term “mediate” is key here. This means that how we explain our material conditions, choices, and their consequences affect what we do in the world and those same material conditions. It also means that our conditions give us the materials to explain our lives. In this way, language makes meaning of our actions and our actions give us language to make meaning. Common sense, then, is both action and language. It’s our verum-factum and verum-certum working dialectically and simultaneously.

But Gramsci isn’t done revamping Marxism. He says that myths, folklore, stories, news media, popular culture, and art are also important ways that dominant forces and groups (those who control things and choices) maintain or control subordinate forces and people. This makes literacy and language classrooms important political sites -- that is, sites where power is exercised in significant ways, ways that control people and create obedience to a dominant group’s language practices.Thus students and teachers have a civic and ethical obligation to question the texts and language practices put forward in classrooms as models and rules for correct or appropriate languaging. Doing this questioning means we question our common senses of our world and of our language practices. Those who control the language and stories we circulate control the ways we understand the world, and control our choices and decisions (note 104). And of course, race and racist discourse are integral to our various ways of languaging and the stories we tell and retell.

Even the very mainstream writer, June Casagrande, agrees with what I’m saying, even if she’s less willing to take a side. Casagrande is a former news reporter and editor of the Los Angeles Times, and author of many books on grammar, style, and English language usage for mainstream audiences. In her book, The Joy of Syntax: A Simple Guide to All the Grammar You Know You Should Know, Casagrande opens with a section called, “So Whose Language Is the Right Language?” She says:One might argue that he goes is standard English and he go is substandard, even though millions upon millions use both regularly. There’s no separating this debate from issues of class, race, geography, and socioeconomic status. The minute someone says x is standard and y is not, they're making a judgment call about whose English reigns supreme. Just as the winners write the history books, the most powerful group of English language users write the grammar books. (note 105)

So Casagrande admits that what passes as acceptable or “good” grammar and style is a part of intersectional politics. She names those politics as based on “class, race, geography, and socioeconomic status.”

Now, Casagrande does not discuss what group has ended up winning the language race wars. She simply admits that the winner has claimed their version to be “Standard English.” Yet even her account of Standard English means that we should be calling it White Standardized English, since if we got specific and historical about this language race war, an elite White group with enough power made their English the standard.

One thing Casagrande does identify correctly that we can translate to our classrooms is this: To call any version of English the “standard” in a classroom and promote it as the correct way, or even just the preferred way in that classroom -- and this includes grading by that standard -- means a political choice based on, among other things, race. It’s White language supremacy.

Our literacy and language classrooms should name such groups of benefactors and beneficiaries, as well as the historical victims of such language politics. Race is one aspect of that political naming. It’s understandable that Casagrande wishes to be equivocal on this topic, but in our own real lives and languaging with others, we live with the consequences of teachers who follow her lead and maintain equivocal stances on language use, thinking that grammar, style, and “good communication” ain’t got nothing to do with the maintenance of elite White groups’ power, that is, with White language supremacy. Or worse, these equivocal teachers think that if they stay out of the fight, if they do not name the elite White English of our academic disciplines, programs, and professions, no harm will be done. This logic is like saying that you can watch a war from the sidelines and somehow you are helping a side in that war by not fighting, by watching them fight.

To clearly understand the problem that the equivocal teacher participates in, more Marxian theory helps. Gramsci shows us that the superstructure can often be part of the base of our lives. From one angle, our stories and languages that we use daily are the ways we make sense of our worlds. They are simultaneously our superstructures and bases. Stories, novels, TV shows, poems, films, tweets, and other social media make, use, and explain race in superstructural ways. They are also experienced as the conditions of our lives -- that is, as the base of our lives. The question then becomes who or what orientation controls such media, such ideas, and the languages used around us? Gramsci’s term for this on-going struggle between dominant and subordinate groups is called “hegemony,” which comes from a Greek word referring to a hegemon, that is, a ruler or ruling power.

One important takeaway from Gramscian hegemony (pronounced: huh-gem-uh-knee) is that it describes the way conflicts that create and move power are not usually about forceful control or coercion -- that’s a last resort for a ruling group. While force can be effective in controlling people, it usually doesn’t last long, and it’s really expensive and devastating to communities. You’ll spend more time fighting people and fixing things than you will enjoying your power and control, if there’s anyone left to control. The language race war is not a conventional war. It’s a war about manufacturing consent (note 106).

Control over people is easier and more effective if those with power can frame themselves as good (and opposed to others who are bad), and circulate stories and ideas that reinforce their goodness. These stories and ideas may even redefine “good” in terms of and from the perspective of the ruling group, the one making the stories -- remember, the victors write the histories, and write themselves as victors. These stories and ideas create consent among those without power by gesturing towards those with less power and their choices in the world. Thus when we consent, it often feels like the exercise of power, like our own decisions and agency.

What choices do we really have, have we had, for how we language in school or college? All of our choices have been neatly arranged in front of us, and the system and its agents have pointed to those choices and said, “go ahead, take your pick.” And we do, and it feels good, and we think we are in control. But our choices have always been constrained, limited -- they have been selected for us and arranged for our choosing -- and we are all pressured to choose that dominant, elite, White English. And we usually do choose it. And it becomes both the verum-factum and verum-certum in our schooling. And this is how we embodied White language supremacy as teachers who end up being agents in the same systems that made our consent to White habits of English language.

Gramsci’s focus on media, news sources, stories, myths, folklore, and language means that an antiracist literacy and language classroom pays attention to these things as common sense, as ways racism is achieved and justified. Hegemonic racist discourse is in everything. It’s everywhere. Thinking of it in terms of hegemony and systemically constructed consciousness lets us ask more pointed questions about the connection between our world today, what we see and do, how we act, and what we say, to those commonly assigned high school texts and novels. How do they uphold the current racial and racist status quo? What messages do they validate or present to us for our consent and circulation?

What about a text like Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird (1960)? It’s a commonly read book in high schools, and often praised for its antiracist messages. Do we really believe that in 2021 our most important questions and issues for high school students about racism and race come from this 1960 novel, a novel by a southern White woman, who as good and thoughtful as she was, surely was influenced by her environment and the racist common sense in it?

It’s a novel written sixty years ago about a period almost hundred years ago. Ultimately, the novel blames all of the problems of racism on the irrational attitudes of individual characters. It’s a novel that leaves the institutionally racist justice system alone and maintains a narrative of a White, male savior (Atticus Finch) for Black people (note 107)? It says racism is about intention, meanness, and bigotry.What lessons and verum-factum does such a novel allow us? What explanations does it encourage us to make of the siege on the Capitol in January 2021 by a mob of almost all White men, some waving Confederate flags, dressed in fatigues, and armed (note 108)? Are these thousands of White men, many wearing “Make American Great Again” hats and t-shirts, all just an anomaly? Did they misunderstand the messages in our society? Are they just the bad people among us doing bad things?

No. More likely, they are made through our racist discourse that we all breathe daily. How would a classroom explore such questions in the reading of Lee’s novel? Who would those rioters align themselves with in the novel, Atticus or Bob Ewell? Like all of us, the rioters see themselves as the heroes of their story, taking back a country stolen, making American great again. Likely, they seem themselves as Atticus.

Teaching this novel as the way to understand today’s racism tacitly sends contradictory and incomplete messages, and constraints students’ choices for what racism is and what we can do about it. It focuses on the racist people -- a mere effect of the system -- not the racist people-making machine -- or the cause of racist people. It lets us too easily ignore the racist discourse, the system, the common sense around us. It says that the voice against racism comes from a White man of the south, and ignores the fact that we all exist alongside a racist legal system that has mostly terrorized and killed Black men to this day, and that we allow to continue working.

The novel doesn’t represent, or even gesture towards, this contradiction. To me, if not carefully read in antiracist ways (note 109), Lee’s novel sounds like a way to redeem White men for the evil done by other White men and their White systems in history, while leaving those racist systems alone. It’s also a way to ignore the real racism today, the racism that makes our classrooms and pedagogies and us.

Essentially, if novels like Lee’s are the main way we bring up race and racism in our classrooms, the tacit message is that racism is a thing of the past, of 1960, or of the mid-1930s if we locate it historically in the story of the novel (note 110). It isn’t that there aren’t important things to learn from Lee’s novel, or even that it shouldn’t be read. There are and it could be. But if we read the novel to appreciate it as literature alone or as an important antiracist message, we miss much of the racist discourse today that uses that novel and its discourse as a panacea for solving White supremacy by ignoring it. We miss the racist verum-certum of the novel as a literary monument to antiracism, and we miss how we, readers, participate in that racist discourse as verum-factum.

High school and college students should understand all this, not to judge the book as bad literature or outdated, but to recognize how ubiquitous racist discourse is, how hard it is to do antiracist work in a world that doesn’t acknowledge the ways that all standards and norms are racist and White supremacist. We live in a world that does White supremacy mostly without naming race, which means we don’t need no evil racist Klansmen to do racism anymore. We all have been enlisted to do that work, and we have consented to it because White language supremacy is the hegemony in all schools, disciplines, and professions.

And because of the hegemony of such stories, oppression becomes preferable systemically-constructed consciousness. This is my term, but Gramsci’s hegemony teaches us this too. Marxist theory tends to call this “false consciousness,” but there ain’t nothing false about a view of the world that says there’s a “Standard English” that is rewarded in a variety of professional spheres. Lots of data back this up, from one perspective. Neither is there anything false about a view of the world that says that that first view misses the language race war that harms most people of color and poor people, and it does it through good intentions and consent to the conditions of White language supremacy. These are just different consciousnesses, different views of the world. But they, like all views of the world, are constructed, but one of them, the first, is made by the system as preferable because it upholds that racist system.

The easiest people to manipulate are those who have few ways to reflect meaningfully on their lives and languaging. By doing this, you can take away their abilities to reflect upon their own conditions. Work them too hard and too long for very little compensation. This allows the system to distract people with simple amusements. Get everyone to watch more movies, play video games, and root for their favorite sports teams for no other reason than enjoyment or some vague, collective sense of togetherness for the sake of winning games in publicly-funded arenas that make money for a couple of White billionaires.

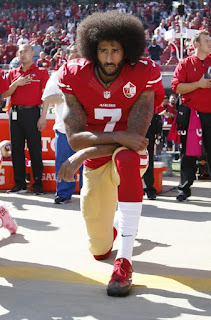

This is why a Black athlete like Colin Kaepernick is so dangerous for the NFL, why no team nor the NFL organization have apologized for excluding him from playing after the 2016 season, and his and other players’ grievances against the NFL were settled out of court for an undisclosed amount of less than $10 million. His kneeling at games during the national anthem was a nonviolent protest against systemic oppression and police violence against Black people in the U.S. It was a disruption in the racist hegemony of football games as allegedly apolitical amusements. But of course, nothing is apolitical in systems made from biases, not a football game, not a national anthem, and not our languaging, nor the standards teachers hold so dear. Kaepernick’s kneeling called attention to the White supremacist systems that even the NFL is deeply wedded too, and it cost him.

What would happen if millions of literacy and language teachers across the country “took a knee” in their classrooms when the official language standards and outcomes were presented? What would happen if we all refused to put our figurative hands on our hearts and pledged allegiance to a single, elite, White English language? What would it cost us? More importantly, what might we gain?

We, literacy and language teachers, are not in the habit of calling out and fighting against White supremacy. Instead we circulate stories and images of those who do such anti-systemic work as crazies, radicals, terrorists, or lunatics, or teachers who are out of touch, not helping their students succeed in tomorrow’s classroom or profession.

One more example of racist common sense that is close to our classrooms. It is the racist Preferable Systematically-Constructed Consciousness of English language style guides and grammar books. I already mentioned June Casagrande as a popular author on such books, but what about the ones in classrooms, our textbooks? I’m gonna put aside that there are very few of these books that are written by writers or editors of color, so few I cannot find one, not one for a classroom in the history of publishing of such books. In fact, if you know of one, please, send me the reference. I would like to read it. Grammar books and style guides have only been written by White, middle- or upper-class, writers and editors from the East coast, and mostly men.

That isn’t what I want to call your attention to though, as obviously White supremacist as that is. When you were a student in your own literacy, language, or English classrooms, did you have an opportunity -- a real opportunity -- to question or resist the language lessons and rules that were in your classrooms’ style guides and grammar books? Were you allowed to investigate them, where they came from, why they were the rules you had to follow, and what consequences those rules of language had to those in the room at that moment? Did anyone even mention that they were all written by elite White people, mostly men, from their places and languaging? Or where you simply asked to learn them and follow them, for your own good because those books contained “correct” or “appropriate” English? What exactly were your language choices and how were they arranged for you?

Over the course of your schooling, did you even think that it was a good idea to resist such common sense as the ideas contained in the grammar and style guides put in front of you? Probably not. This is the verum-certum of English style guides and grammar books in classrooms. And those books also embody the verum-factum that make them common sense. The systems of teaching, schools, and textbooks all conspire in numerous ways to uphold and validate as common sense White language supremacy. And you, like the rest of us who made it as teachers, chose White language supremacy, chose to fight for it one bullet at a time.

And of course, we might ask about the classrooms we now teach in: How do you use your grammar books and style guides? What are the language choices you arrange for your students? What pressures exist for them when they make their choices? Is their situation any different from your schooling? How do you help your students question, counter, and resist such racist common sense?

Are your students allowed to take a knee when it comes to your standards of English languaging? This is the language race war. And we participate by manufacturing the conditions that make for our students’ consent.

This blogbook is offered for free in order to engage language and literacy teachers of all levels in antiracist work and dialogue. The hope is that it will help raise enough money to do more substantial and ongoing antiracist work by funding the Asao and Kelly Inoue Antiracist Teaching Endowment, housed at Oregon State University. Read more about the endowment on my endowment page. Please consider donating as much as you can to the endowment. Thank you for your help and engagement.

Comments

Post a Comment