Blogbook -- The Difficulty of Avoiding White Language Supremacy in Standards

Entry 38

If what I’m saying about learning outcomes and standards for language seem counterintuitive or wrong, it’s because the systems we live in are built on whiteness (see post 28 on HOWL), and that whiteness is hard to recognize as politicized or positional (that is, biased). Whiteness is a deep part of the structures that make us as teachers, our languaging, the CCSS, and the OS. The CCSS validation committee (listed in Reaching Higher: The Common Core State Standards Validation Committee), is a collection of national experts and teachers, and they illustrate the problem I’m speaking of. The problem of white language supremacy is in part embodied in the whiteness of the people who created and validated the CCSS. The CCSS validation committee “was charged with providing independent, expert validation of the process of identifying the Common Core State Standards as part of the CCSSI” (note 256). This committee essentially checked the work of the numerous other working groups and committees that built the CCSS. This isn’t that uncommon in academic circles. The WPA OS had a similar process of validating ideas for its culminating document. I’ll come back to this.

The CCSS’ validation committee’s 2010 report lists the full committee and its two co-chairs. Of the 27 members listed, I could identify only three members of color (one man from China, who was a mathematics professor, one Japanese man, and one Black woman) from their online bios and faculty pages. The committee had only ten women, nine of them white. This means only about a third of its members were women. The two co-chairs were both men, one white (a professor of education policy) and one Asian (an assessment expert). The overwhelming dispositions of the validation committee were white and male (note 257).

These were the experts. They were produced in the usual places that white supremacist systems like schools and universities produce such experts. I have no doubt they all embodied in various ways habits of elite white language, since they all were accomplished experts in their fields. To be an expert like them, it requires that you master such language habits in order to succeed, to get a job as a professor or researcher, then be asked to be on such an important committee. They aren’t bad people, I’m sure, but they are a particular kind of people.

If they are not explicitly trying to, however, this arrangement reproduces only a narrow kind of languaging as standards. And the report, which explains the committee’s purpose and goals, does not mention any antiracist goals, nor a purpose of countering or dismantling white language supremacy or anything of that nature. Not considering such things as antiracist orientations or work is a habit of white language that usually understands language work as neutral, apolitical work. From my experience, this has also been a disposition of white groups of people in academia and elsewhere.

These kinds of demographics and habits of white language are not unusual in university writing programs either. This is another key place that creates or influences the CCSS. When the CCSS says colleges expect logocentric writing, they are talking about first-year writing courses as one of those places. These writing programs are also the places that teach and do research on college writing. The structural whiteness is so ubiquitous in writing programs that it has gone mostly unnoticed until the last few years. Recently many college and university writing programs have begun to pay attention to their whiteness and the problems of racism and access it causes (note 258).

Brave Work

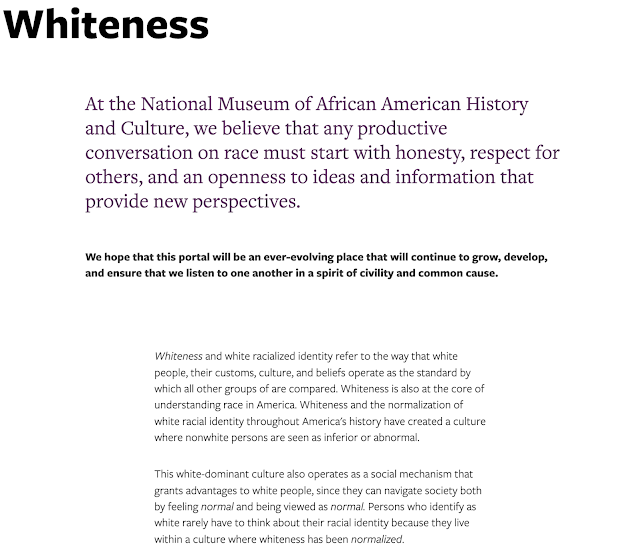

Take 2-3 minutes to read and think on the screen capture below from the webpage on "Whiteness" from the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Spend 5 minutes writing on what the whiteness means in your own classroom or department at your institution in your daily actions and interactions.

In fact, last year (2020), I was asked to co-chair a task force for the Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), a leading national organization whose members are the professors and administrators who design, manage, and teach first-year writing courses at colleges and universities across the country. This task force was charged to revise the long-standing and influential WPA Outcomes Statement (the OS that I’ve been discussing since post 29) to include explicitly antiracist and anti-white supremacist language and concepts (you can see what we produced in my post, “First-Year Composition Goals Statement”) (note 259). That process ended badly and the executive board of the CWPA declined to accept our recommendations (see my post “Why I Left the CWPA” for an account of what happened).

The OS is a key document used to design the learning outcomes and curricula of most writing programs in the U.S., either directly or indirectly. Many universities use the OS as their learning outcomes for first year writing courses. It is very similar to the CCSS in function and language, only the OS is broader and less directive than the CCSS. Yet the outcomes it offers writing classrooms draw heavily on habits of white language and Eurocentric assumptions about language and rhetoric, just as the CCSS does. It’s a way college classrooms participate in language empire building if they aren’t oriented against the OS, even as they may be required to use those outcomes, even as there are good things to learn from the broader goals (not outcomes) that the OS puts forward. This is what our CWPA task force attempted to do in our revisions.As a comparison to the CCSS validation committee, consider our task force’s members, a kind of antiracist validation committee, one that by design resisted the whiteness of the discipline and the very organization that called us together. Our task force was made up of six writing experts from across the country, all of whom are BIPOC, with two co-chairs, one white woman and me, a BIPOC man. Thus seven of the eight college writing experts working on the revisions to the WPA Outcomes Statement are BIPOC, and four are women (note 260). All the writing experts on this task force have commitments, experiences, or scholarship in the areas of antiracism, linguistic justice, and multilingualism. They also represent researchers who do research in writing and rhetoric with or about key racial groups traditionally missing from the CWPA as an organization and have been absent in past deliberations on the WPA OS. That statement itself has gone through three versions, the last revision was approved in 2014. The vast majority of those involved in writing the original OS were white (note 261).

So asking a task force of almost all BIPOC scholars to revise the OS to be more antiracist was a significant move in an overwhelmingly white organization and field (note 262). These moves suggested that even the leadership of such a national organization realized the white language supremacy they perpetuate and wanted to make changes. The problem of whiteness in the CWPA likely wasn’t new to anyone on the executive board, as I had given a plenary address at the national conference in the summer of 2016 on this subject. In the case of our task force members, several received free memberships from the CWPA, because they were not members and the organization knew they needed BIPOC experts to do this work, so they looked outside of the CWPA and made efforts toward inclusion.

But even this knowledge and awareness did not lead to accepting the changes we offered. That is, the changes we put forward were rejected and questioned by the CWPA’s executive board. They turned down the changes. They kept telling us that they loved what we were saying in the new document. They agreed, in fact. But it didn’t seem usable or understandable to the typical college writing teacher, or for programs to use in things like programmatic assessment processes.

The problem as I see it now wasn’t just that we, the mostly BIPOC task force, produced a new antiracist version of the OS. It was also that we didn’t replicate the whiteness they understood others would expect from such a document. This was a case where the good intentions for antiracism were inadequate to make for antiracist changes. It is difficult to avoid the white language supremacy around us, even when we know it exists and want to change it, as I know the executive board of the CWPA wanted to. It requires in such cases broad agreement about the antiracist orientation folks will exercise as they make decisions.

Whiteness of the PAC 12 Writing Programs

As another way to see the white language supremacy problem, take the twelve universities that make up the Pac-12 collegiate conference. Of the twelve major universities, of which I work in one (ASU) and have worked in three others (OSU, WSU, and UW), currently there is one Black male writing program administrator or director (Stanford). He is the only faculty of color directing any of these university writing programs as of fall 2021. The rest of the directors are white. Seven of them are white women. The director leads the program, makes curricula, hires and trains teachers, assesses the program for effectiveness, uses (or ignores) the WPA OS, among other things. These are not atypical demographics for such programs across the country. The Pac-12 is not the exception. It demonstrates the rule.

It’s not hard to see that habits of white language, as well as characteristics of white supremacy culture, are structured into writing in college without anyone trying to do this. It’s an overdetermined system -- that is, there are multiple, overlapping, and redundant ways the system is racially white and maintains white language supremacy. Let me reiterate: None of these writing program administrators or professors are bad people. One would be hard pressed to find a racist among them. But I wonder how many have explicit antiracist orientations, ones that position them against such sacred cows as the WPA OS?I’ve yet to hear anyone until this year directly critique the outcomes statement as white supremacist (note 263). I’ve yet to see any program systematically redesign and remake their outcomes and courses in antiracist ways. A few programs are involved in that work, but they usually start by helping faculty understand what antiracist work is. This is vital, but it means that the outcomes and standards, the structures that make such writing programs continue to exist and exert their power as white-language-supremacist-place-making entities. It also tells you just how deep white language supremacy goes. The structures are in all of us, and so they are hard to avoid.

What this ends up meaning for everyone is that usually things like learning outcomes for language seem neutral. They seem just about language, rhetoric, and writing. So it makes perfect sense to base the CCSS after what colleges do, but does it make ethical sense, given our sociolinguistically and raciolinguistically diverse high school students? Does it make sense given that almost half of all high school students will not write in or for college purposes, at least not immediately? Does it make sense knowing that the outcomes of such writing programs favor an elite white racial group by disadvantaging other groups? Does it make sense knowing that there are many different and equally communicative Englishes functioning in the world already that could be used in schools or college classrooms?

Whiteness in the Authorlessness of Outcomes

Just like the authors of the WPA OS, the CCSS appears to have no authors. Both documents are offered as anonymous, or rather, the authors are not identified, and it is hard to find a list of them. Leaving key documents like these seemingly anonymous easily reproduces white supremacist outcomes by hiding the whiteness of the authors, their backgrounds, and their languaging. This practice is often meant to validate the claims and arguments offered, making them only attributable to the organization or group publishing the report or document. It’s meant to give authority, weight, and ethos to the document. It’s meant to show that the ideas or document is from the organization or school, not the opinions of individuals, who are subjective and biased. It is meant to avoid the criticism some may have of individuals who have politics and their own perspectives, as well as protect individuals who do such work. But it also erases the subjective nature of outcomes and standards, such as the OS and the CCSS. Presenting documents like these without authors hides their inherent racial politics, and given the nature of our disciplines, it also hides whiteness.

We know that a group of people, who are gendered and raced, who come from particular places with particular habits of language, made this document, crafted the words, made judgements to include or exclude ideas, even though in both cases, the groups were quite large. When read anonymously, the ideas and arguments of the CCSS seem to just be, to exist with no bodies or politics and self-interests. But of course, this is a fiction. The seeming anonymity of both the OS and the CCSS exercises one common habit of white language: a stance of neutrality, objectivity, and apoliticality.

It’s hard to avoid this problem in both documents, I admit, as the list of authors or contributors likely would be very long. But what about a description of the racial, gender, and other social positionings of all who participated? What about revealing the demographics and postionalities involved in some detailed way? We do this for all studies and research. It’s not like we don’t have methods and ways to explain who the people involved in such projects are. The need by those in charge to create a veneer of objectivity and neutrality in such documents keeps most programs, schools, and organizations from confronting their own biases and subjectivities and revealing them in ethical ways when circulating their outcomes and standards. But this, then, would also mean that those biases and subject positions, as well as the outcomes and standards that come from them, would be open for scrutiny and debate, something whiteness has rarely been willing to do.

This blog is offered for free in order to engage language and literacy teachers of all levels in antiracist work and dialogue. The hope is that it will help raise enough money to do more substantial and ongoing antiracist work by funding the Asao and Kelly Inoue Antiracist Teaching Endowment, housed at Oregon State University. Read more about the endowment on my endowment page. Please consider donating to the endowment. Thank you for your help and engagement.

Comments

Post a Comment