Blogbook -- What's the Problem With Most Standards and Outcomes

Entry 29

In the first half of this blogbook (entries 1-28), I’ve offered a history and theory of racism that might be helpful to literacy teachers. In that theory, I discussed race as a concept and set of structures that have infiltrated every aspect of our lives and education, including language -- that is, how and why we talk to each other, and who we talk to. I ended that section of posts by offering twelve habits of antiracist teachers (entry 22). I then provide a discussion of white language supremacy, what it is and how to confront it in our literacy and language classrooms. I ended this section by offering six habits of white language (HOWL) as a reflective heuristic (entry 28). Now, I’d like to try to put this all into a kind of practice. That is, I’ll apply these ideas to something we all have contact with as teachers: literacy standards and outcomes.One way to see the ways that racist discourse and white language supremacy in secondary schools and postsecondary education exist is to look at the use of standards and learning outcomes. Standards and student learning outcomes (SLOs) dictate curricula, lessons, testing, and the assessment of student learning in all kinds of ways. Regardless of the details of any individual classroom’s standards or SLOs, all are informed by racist discourse because of the histories and disciplines that have made them, as I've discussed already in this blogbook.

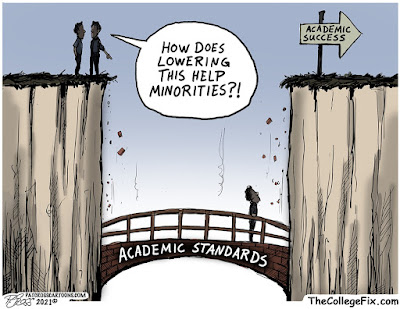

These conditions makes arguments like those displayed in the Pat Cross political cartoon (above) not simply false but misleading. It sets up the discussion of standards in college or high school classrooms as one about lowering or maintaining academic standards. It assumes that because we've seemingly always worked from the idea that we need universal standards for every student that when we critique or change or rethink standards, we are "lowering" our standards. This argument and its necessary assumptions misunderstands what standards and outcomes are, where they came from, and how they operate in literacy classrooms. It is clearly made by someone who has not taught students or studied language.

In the secondary and postsecondary language and literacy classroom, all standards for language and SLOs are produced or influenced by an elite, white racial formation in history. I’m talkin about HOWL. Reiterated in the figure to the right, HOWL is a set of structures that are simultaneously outside and inside all of us. They are institutionalized language habits, practices, policies, and behaviors that make up our stated outcomes and standards, teacher training, and disciplinary knowledge and expertise. They are around us and a part of us as academics and teachers. This makes HOWL very difficult to avoid in our standards and SLOs, and in the way teachers use them to make judgements about students’ literacy performances. And of course, HOWL plays an important part in reproducing conditions of white language supremacy.What I focus on in the coming blogbook posts (this chapter) is one common set of standards for secondary classrooms, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) for high school language classrooms and the CWPA Outcomes Statement (OS) for postsecondary writing courses. I consider how racist discourse influences these common kinds of outcomes in their design and use in schools, which often turns into white language supremacy (WLS). I pay particular attention to the way the habits of white language and judgement (HOWL) are activated in such outcomes and standards in ways that make white language supremacy in classrooms. I discuss the CCSS and OS in this chapter only because they are specific known examples. All standards and SLOs function in the same ways. The lessons we can learn from them apply to all standards, no matter their exact wording.

Now, I’ve never taught using the CCSS. I’ve never been a high school teacher. But I’ve talked to enough high school teachers in workshops and other professional development situations over the years to know that how standards get implemented in schools is at best problematic and contentious. And of course, I’ve designed and assessed programmatically enough writing courses in college settings to understand how such universal outcomes and standards work in racist ways. I've directed two different university writing programs and been an associate dean of a college with several writing programs in it. I’ve also been a part of large scale testing administrations that use similar kinds of standards to score high school student writing, such as the AP Language exam.

I should also say that in the following posts I often use the terms “outcomes” and “standards” together, but they are not synonymous. In assessment circles, they are not exactly the same. An outcome often references a task to accomplish or a discrete thing students are expected to demonstrate by the end of a course of study. For instance, an outcome for a writing course might be to be able to summarize a text or understand particular concepts like ethos, pathos, and logos. Usually outcomes require that a teacher or judge decide if a student has met that outcome or demonstrated it in a performance of some kind in some adequate or proficient way.

This kind of judging is a ranking of performances. In literacy and language classrooms, it requires HOWL to operate -- that is, to determine what kind of literacy performance is adequate. More crucially, language-based outcomes tend to be made by and from HOWL. They are HOWL institutionalized. Remember, HOWL consists of the language habits, practices, policies, and behaviors that the academy and schools are made of and promote. These conditions create invisible ways HOWL reproduces white language supremacy from any of our outcomes. To see proof of this, all we have to do is look at the results, the racialized consequences of universalized literacy outcomes in schools -- that is, who tends to do better and who worse?

A standard, on the other hand, is usually a description of the way an outcome is judged along a linear or hierarchical scale. That scale could be numbered (0-100), lettered (A-F), or identified by terms, such as “proficient,” “emerging,” or “developing.” So for any outcome, a course or program might identify standards that categorize student performances on a scale. Articulated or stated standards are often a way to guide teachers’ judgements of any demonstration of an outcome by students, say in a final essay or a portfolio. It’s also a way to rank students by each outcome, say, using a rubric to score those essays or portfolios. Even holistic scoring does this.

The simplest scale is a binary one: proficient or not proficient, pass or fail. While less hierarchical than more elaborate scales (e.g. 1-5 or A-F), a binary scale is still a scale and a hierarchy. It’s a standard based on categorizing students into two groups along some dimension. One group is always better than or preferred over the other. And this categorization uses teachers’ HOWLing to put students into the two categories, out of necessity. When used in classrooms, all standards require teachers to use their HOWLing to judge language performances and rank them.

And of course, we should remember that a teacher’s judgement of a student’s performance, say as meeting the standard for proficiency, is NOT that standard. It is one judge’s judgement of it, one translation among many other possible ones, all of which are based on the same stated standard. This problem with the nature of standards, much like the use of outcomes that draw on HOWL in their articulations, easily reproduces white language supremacy through the HOWLing teachers must use to judge. In short, WLS is overdetermined in educational systems by the nature of our standards or outcomes and the various and uneven ways teachers judge students from their own HOWLing.

Yet another problem with standards and outcomes is how they often dictate assessments and testing, which then have a direct impact on what teachers can teach and how they teach in their classrooms. In the assessment community, this dynamic is called “washback.” It’s when a test or assessment, usually large-scale and standardized, dictates what happens in classrooms and schools because those courses and schools are meant to help students do well on that test. So schools require teachers to teach to the test because the test is the real goal, not student learning.

The test, then, which comes chronologically later than student learning but first in the design of curricula, washes back into the classroom, determining what goes on there. This is “teaching to the test” -- notice, it ain’t learning for the test. And this is the problem. It’s all in where the assessment focus is, what the assessment ecology bends toward. In the washback model of teaching and learning, student learning is an indirect byproduct of high test scores. Student learning is incidental to the real goal: high test scores. But the rationale for such tests is that the test indicates how much learning a student has acquired. Tests that wash back into classrooms create pressures to teach particular outcomes and judge students in particular ways, which end up harming many students who do not have histories with language that predispose them to the biases of the test. In short, tests that wash back into classrooms also create conditions of WLS.

The point I’m making here is that outcomes, standards, and the required tests that wash back into curricula and classrooms reproduce WLS in a number of ways. WLS is the overdetermined conditions of teaching and learning in all literacy classrooms. This is because our outcomes are made from HOWL; our judging uses our HOWLing against students to rank them along those outcomes; and the larger teaching and learning conditions pressure us to teach our HOWLing, then reward or punish students based on our sense of their abilities to mimic such HOWLing.

In the next few blogbook posts, I’ll look closer at standards and outcomes in classrooms. I'll start with the Common Core State Standards, then move to the WPA Outcomes Statement for college writing courses. These are two common examples that can be a part of the overdetermined way we all participate in WLS if we are not very conscious and careful in our classrooms.

This blog is offered for free in order to engage language and literacy teachers of all levels in antiracist work and dialogue. The hope is that it will help raise enough money to do more substantial and ongoing antiracist work by funding the Asao and Kelly Inoue Antiracist Teaching Endowment, housed at Oregon State University. Read more about the endowment on my endowment page. Please consider donating to the endowment. Thank you for your help and engagement.

Comments

Post a Comment