A Response to Paul Beehler -- Part 1 of 3

My good friend and colleague, Vershawn Ashanti Young, suggested I write a response because the article required it. So here's the first installment of three posts over next week or so.

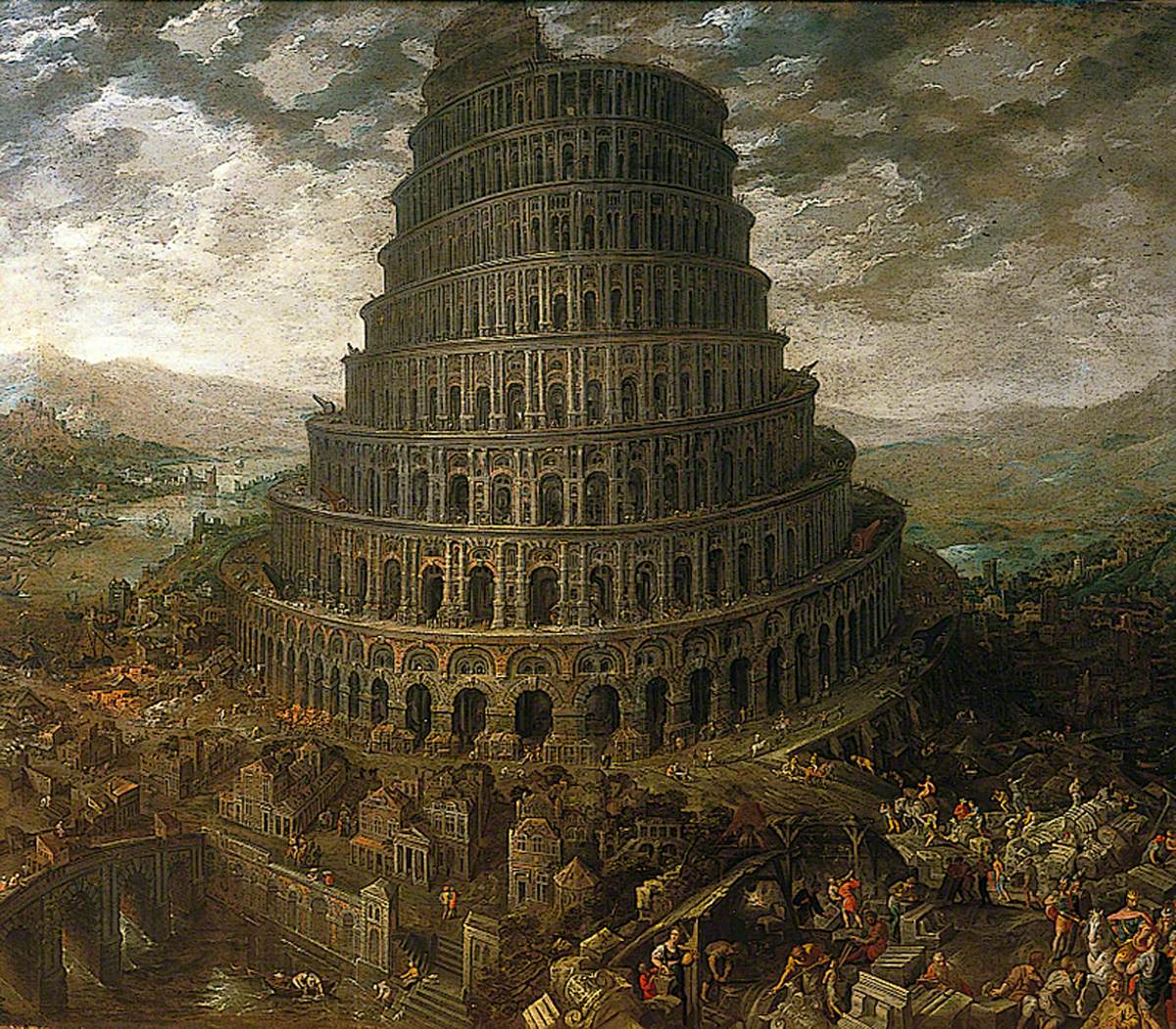

Thinkin' Bout Towers and Strunk & White's Babel

In his article, “Cracking the Code (Meshing and Switching): Standard English as a Required Ticket to Influence,” Paul A. J. Beehler argues that it is essential that writing teachers and schools promote and teach a single standardized English, suggesting that it need not be associated with a white racial group of language users, and that it is a key to future success in our society, a society that already uses and favors such an English. I appreciate Beehler’s thoughtful discussion and share his concerns for the success and wellbeing of college writing students today. I know we work toward the same goals, but ultimately, I find Beehler's arguments, most of them, misguided.

|

| "Tower of Babel" Tobias Verhaecht (1560-1631) |

There are other ways to read the story though. A unifying language is not possible in the actual material world, even if ironically it is ideal. We can strive toward and dream of a common English, but because of how language exists and circulates in our world, it ain’t possible. We inherit a world of multiple languages and diverse people. These are our conditions. We must work with them, not against them. Further, if you take God’s side of the story, humans are not made to have a unified language. It’s not how languages work, nor how people work. Our differences in cultures and languages come from the differences in our various different material conditions, our different histories, geographies, etc. God’s plan ain’t for us to build a tower to them. They come to you (I use the plural pronoun for a divine reality that does not have gender). If you don’t believe in a divine being, then the metaphor could be a set of cultural paradoxes:

- We cannot have a unifying language, yet we yearn and strive toward it, even as we realize it’s impossibility.

- We try to build our towers toward (or to ward off) God but cannot fully accomplish this task, yet we keep trying.

- Language(s) is both unifying and separating.

I am not suggesting that Beehler’s reading of the Babel story is wrong, only that I notice other ways to read such a myth that complicate his reading of things. And my more paradoxical reading of the story also reveals limitations to Beehler’s other arguments that promote a single standard of English to be taught and assessed in college writing classrooms. There appears always to be a god-like force in the real world that disrupts our unifying language efforts, even as those efforts may be worthwhile to pursue. The question really is, as I see it: How do we pursue such efforts with our students equitably, and in just and sustainable ways? I think, Beehler would agree with such a question.

One thing that hurts his argument is how he defines his key idea. Beehler avoids defining the very thing that is at the center of his discussion, a standardized English. Instead he offers only a footnote that is meant to explain what he means when he says, “Standard English.” Here's the footnote:

I accept that Beehler’s present discussion is not meant to define the process of Standard English, but certainly more than gesturing to Strunk and White’s book, a most problematic yet highly influential text, is necessary when such a construct is central to his argument. Here’s what I know about all style guides like Strunk and White’s. They are written by white, middle to upper class, monolingual English speaking men from primarily the East coast and elite schools in the U.S.

William Strunk was E.B. White’s professor at Cornell. They both come from well to do families. Strunk’s father was a teacher and lawyer in Cincinnati, White’s was the president of a piano firm in New York, and his mother was the sister of the American painter, William Hart. This is the pattern of all such style guide authors. The language group of such authors is a hegemonic group that has made standards for language use because they’ve always had the power to do so. This fact is important to come to terms with when one considers language standards and how such things will be taught or assessed in any college writing classroom today because most students do not come from such places as Strunk and White. In fact, most people will not use language with such people in such places in their futures, and there are no reasons they should. This is not the same as saying they cannot or do not have the ability to, given enough time and personal reasons to do so.

I could criticize Strunk and White’s book on a number of other accounts, such as their misogynistic way of arguing against gender inclusive pronoun use, but that is not my purpose here. You can find a discussion of whiteness in Strunk and White in Laura Lisabeth's (SUNY Stony Brook) blog and her article in Radical Teacher (Fall 2019, pp. 21-26). Here, I reveal Beehler’s politics, a whitely politics that ignores its own power relations, a politics that assumes language standards promoted in a classroom can be outside of the politics of race. Just like Strunk and White’s politics in their handbook, for Beehler it doesn’t matter where such standards come from or who attempts to circulate them. This is not what I believe. Beehler wishes to build a tower from an impossible common language, one doomed to crumble into innumerable languages, each unique and interesting, each its own tower.

Read the second of three installments in this extended critique.

Comments

Post a Comment