White Supremacy of SLOs and Grades -- Part 2 of 3

This post is part two in a three-part series that responds to Erik Armstrong's (@mr_e_armstrong) Tweet. Thank you, Erik, for asking these questions. If you haven't, read part one.

How well do SLOs, or Student Learning Outcomes, work with labor-based grading systems? Most college writing programs and high school English courses have SLOs of some kind. They are often used to do a number of things: identify key competencies that students are supposed to learn; help determine curricula; and provide the specific things that programs can assess in order to understand how effective their courses or program is. Do labor-based grading systems in writing classrooms contradict or ignore SLOs? Can you use a labor-based grading system in a course that has SLOs already determining much of what goes on in the course?

The short answer is, yes. A much longer answer is in chapter seven of my book, Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom. But in this blog post, I'll offer a shorter version of that longer answer.

The Unreliability of Our Quality Judgements

Here's the issue for many writing teachers and educators: If a teacher uses a labor-based grading system, they are not using a quality-based one, or one in which the teacher determines grades in the course by their own judgements of quality of student performances. Those judgements allegedly are an accurate enough measure of the standard for writing or communication set by the program through their SLOs. In short, using a labor-based grading system can mean not teaching to standards or outcomes established by a program or school. The result is that students do not learn what the course is meant to provide them.

But there is a hidden problem concerning judgement in this logic. And we gotta talk about it before we can even get to understanding SLOs. The two concerns are connected.

The problem is a classic one in psychological measurement. Can any teacher measure something like SLOs in their students' performances the same way as other teachers will in the same school or department? Additionally, can any single teacher measure their own students' literacy performances the same way every time? Can teachers be consistent in their grading of quality writing in classrooms? If you have a standard, and you say you use it to evaluate student performances, you better be consistent, or you'll be unfair to your students. These are questions of reliability.

What the research shows is that we teachers of writing, like everyone else, are not that reliable when it comes to evaluating literacy performances, no matter the standard used. This is how human judgement and literacy work together. It's also paradoxically why it's a good idea to get lots of responses or feedback on your writing before you finish it. The more people who give you feedback, the more kinds of judgements you'll get, and this means, you'll have richer and more valuable information to make changes. But in a situation where grades and evaluations mean granting or withholding opportunities from students, then this unreliability or inconsistency in how people evaluate language is a problem of fairness. It's also a problem of learning too, since why would any smart or savvy student listen to their peers' feedback when the teacher is the only one grading their final drafts?

In a famous 1961 ETS study conducted by Paul Diederich, John French, and Sydell Carlton, the researchers found that the correlations among English teachers evaluating and grading the same set of college first-year writing papers was .41, which is quite low (that's not good reliability). This number identifies the amount of agreement among readers. In statistical terms, it is a measure of linear association on a scatter chart of all plotted grades to all papers in the study. If you square this number, you get a percentage that represents the response variable variation that is explained by your linear model (the scatter chart). What does this mean? It means this percentage is the amount of agreement in your model.

How much did teachers agree? In this case, squaring .41 turns out to be .1681 -- that's just under 17%. So what these researchers found was that when they gave the same 300 papers to 10 English teachers, those readers only agreed about 17% percent of the time on grades given to all those papers, while the full set of 53 readers had even lower correlation of .31, or about 10% agreement. So, even if a group of teachers are off by a small margin in how they evaluate student performances in their classrooms, the results can be quite large in effect when measured across many students and graders. But disagreement is often quite large when it comes to language. What the Diederich, French, and Carlton study show is that agreement among readers who are not normed to each other, even when they are highly specialized and trained in a discipline, like English teachers, are quite random in their evaluations of literacy.

Few Schools, Departments, or Programs Assess Their SLOs

The above problems with the reliability of teacher judgement makes the use of SLOs -- which demands that judgements in classrooms be uniform and consistent if those classrooms are fair and accurate -- dubious and dangerous. I've yet to meet a college writing program, or a high school English department that had installed processes that could reasonably assure that the SLOs they have for their courses are measured reliably. And I'm putting aside the problems with where those SLOs come from, who they privilege, and who they harm. I'm simply talking about using them responsibly and ethically in the ways we say we use them. Usually, from what I can tell, programs use SLOs to say they are doing their job, but having SLOs and assessing them are very different things. The first is easy to do and means very little. The second is very hard to do and very expensive.

If a school or classroom is gonna use SLOs to say they are holding students to particular standards of language, then they better have formalized ways to validate whatever decisions they make from classroom grades of writing quality. What does this mean? It means, you need a number of things outside that classroom to assure that what's happening in it is fair. Below is one of the simplest sets of requirements I can think of, and it should illustrate why such procedures are not done in most schools and how costly and time-intensive they are.

Without some version of the above assessment elements happening regularly, the use of SLOs is very dangerous. Why? Beyond the unreliable or inconsistent grades and outcomes that likely will occur in a system that is predicated on the opposite, SLOs end up hurting particular groups of students for no good reason. The students are whom you'd expect: students of color, multilingual, and those students who do not come to the classroom already using the language standards and habits in the SLOs. SLOs create a funnel and filter of opportunity, one takes a large group of diverse people and rewards a few of them. A few make it through the funnel and filter. This is how white language supremacy operates.

The White Supremacy of SLOs

But we can also argue against the very idea of SLOs by looking at where they come from, who is in charge of judging for them in student performances, what their training is, who benefits, and who is likely disenfranchised from all these patterns. And there are patterns, ones you likely can anticipate. These patterns are classed, raced, and gendered because our educational systems, our ways of training teachers, our classroom pedagogies, our society and all that it produces is based on a white supremacist set of assumptions, rules, and habits which reproduces such patterns in teachers and administrators.

In this case, what gets reproduced in the use of SLOs are the habits of white, middle- to upper class, monolingual English language users (see this post and this one to read more about this), which then reproduces people with just those language habits in future teachers and administrators. Just to give a quick sense of one side of this problem, here's a graph from the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) that shows the demographics of full-time college faculty in the U.S. in 2017.

Now, this represents only 1.5 million full-time teachers from across all disciplines, which are only 53% of all faculty who teach at the postsecondary level. So while these numbers will likely look different in that part-time group, and in English departments and Writing programs, my sense of visiting many writing programs and English departments over the last fifteen or twenty years is that they represent the kind of racial and gender disparities that affect who judges those SLOs in writing classrooms.

What I want you to notice is that in the instructor and lecturer categories, the groups of faculty most likely to be teaching first-year writing courses, between 76%-80% are white, more are women, and very few are black males. These are the folks who teach writing in college, and it should include all those part-time faculty not in the above graph and graduate teaching assistants but it doesn't. I've visited 36 different college and university writing programs and English departments in just the last two and a half years for various reasons, without exception, their writing teachers are predominantly white and female. Their grad students are the same. The above graph likely doesn't look that different if you included all those who teach writing courses in college. In fact, it very well may be even more skewed toward white teachers.

Of course, being white and female ain't a bad thing and it doesn't tell us one's linguistic proclivities, but it does suggest patterns that are real. It also suggests a few things about one's relationship to language and to the educational structures in the U.S., things beyond good intentions and ideals of fairness to all. How do you think one gets the privilege of being a writing teacher, even a graduate teaching assistant? You demonstrate the habits of language and judgement that are common in the discipline, in academia, and in the groups who established those places, namely white, middle- to upper-class, monolingual English speaking men. This means that no matter how wonderfully stated your SLOs are, they likely will be used as a white supremacist tool. It's how the system works. It's unfair to a significant number of students.

Grades vs. SLOs

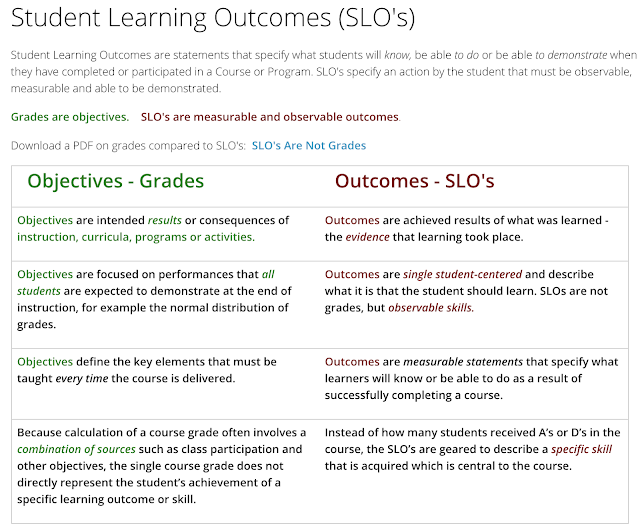

Oxnard College offers a clear explanation of SLOs verses grades, which illustrates both the attraction to SLOs by departments and programs and the problem I'm describing above.

As the webpage above states, grades are not SLOs. This means that using quality-based grades does not mean you are following or even administering SLOs. It means you are grading by a standard you've set. They call it an "objective" and it's essentially one step removed from the learning that any course or teacher is attempting to teach or assess.

In fact, grades often are a problem in classrooms that are dictated by SLOs. As the Oxnard page tries to make clear, teachers get confused between grades and SLOs. That is, when a teacher uses grades of quality, they often can be fooled into thinking that they are measuring outcomes, but that is not necessarily the case. And since SLOs and grades are not the same things, a teacher can be using SLOs in their classroom, but grading students based on their own privatized objectives (that likely are not fully clear to the teacher). So if you care about SLOs, then you should be more inclined to get rid of the confusing practice of grades.

The easiest way to understand this distinction between grades and SLOs is to think of grades as a teacher's objectives and these objectives are measured typically by a number or grade. SLOs are outcomes, or the products of learning in a system or course understood or seen in students' performances. So SLOs tend to be quite specific actions or products, much more so than objectives, since objectives are actually subjective -- they are the teacher's understanding or judgement of the results they (think they) see in a group of students. Grades as objectives are like the teacher's translation of the essay that they read. Grades ain't the essay, but what the teachers thinks of the essay. SLOs are the student's essay.

And because there are many paths to any final course grade, grades are not compatible with SLOs if those grades are mean to be some measure of SLOs. So my first concern about the unreliability of individual teachers is often what makes grades so problematic. In short, grades are a horrible measure of course or programmatic effectiveness, especially if SLOs are used to define such terms. And SLOs, because they are more specific and require very particular products to be demonstrated in student performances -- think the funnel and filter -- they too are a problem. They are white supremacist.

WPA Outcomes Statement and White Supremacy

SLOs embrace white habits of language and judgement in how they get used, or how they have to be used by default in classrooms. Remember who gets to be writing and English teachers, where they come from, and what they must demonstrate in order to be teachers. Who do you think creates the SLOs for any course or program? Cycles of reproduction.

The most commonly used outcomes for writing programs in colleges and universities is the WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition. Developed by a distinguished group of writing researchers working under the auspices of the Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), it was first published in 1999 and has been revised two times since then. Its most current version was updated in 2014. Many programs use the Outcomes Statement either as their writing program outcomes or as a starting place to develop their own. I'll offer just one example from the Outcomes Statement to illustrate how such a document has a hard time escaping the white supremacist outcomes it inevitably reproduces, even when good, smart, ethical people use them.

Here's one set of outcomes from the first-year writing program at my institution, ASU. While I'm not a member of that department or program, I know everyone. The web page that offers their program goals references the WPA Outcomes Statement and clearly it has influenced their SLOs. Rhetorical knowledge is the goal, and what that means in terms of outcomes that students will do is listed below it.

Now, there is nothing inherently wrong with these SLOs. I don't find their articulation to be white supremacist. It is in how they are judged and used in classrooms that makes them so. If writing teachers come from mostly white, middle- to upper-class, monolingual English speaking places, and they require such habits of language to be bestowed the privilege of teaching writing at a school, then how do we think something like "use heuristics to analyze places, histories, and cultures" will be understood, seen, and evaluated in a writing course? It's up to the teacher to decide what exactly this slippery outcome actually looks like. The funnel and filter is still in place, even if you don't use grades.

How teachers understand what these outcomes look like in student performances is crucial to the maintenance of white language supremacy. And most of the time, teachers do not realize they are participating in white language supremacy. In fact, the reproduction of white language supremacy requires that teachers NOT realize they are doing it. If they did, most would stop and do something else.

There is a lot more to talk about. I could go through the WPA Outcomes or any set and discuss the ways white habits of language both influence those outcomes or how teachers must use them from their own white habits of language and judgement, but I'll hold off here. I'll say that judgements that lead to grades usually are the key to white language supremacy.

I'll end by saying that SLOs and grading often work together to produce white language supremacy, and unfairness in classrooms. There are good things to see in SLOs, but lots of bad stuff too. Labor-based grading contracts do not solve all of these problems, but they do make for a classroom ecology without grades, and they offer students a choice to be funneled and filtered, or not. I think, that is important in producing a fair enough classroom ecology.

How well do SLOs, or Student Learning Outcomes, work with labor-based grading systems? Most college writing programs and high school English courses have SLOs of some kind. They are often used to do a number of things: identify key competencies that students are supposed to learn; help determine curricula; and provide the specific things that programs can assess in order to understand how effective their courses or program is. Do labor-based grading systems in writing classrooms contradict or ignore SLOs? Can you use a labor-based grading system in a course that has SLOs already determining much of what goes on in the course?

|

| Photo by CZ, "Spring" |

The short answer is, yes. A much longer answer is in chapter seven of my book, Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom. But in this blog post, I'll offer a shorter version of that longer answer.

The Unreliability of Our Quality Judgements

Here's the issue for many writing teachers and educators: If a teacher uses a labor-based grading system, they are not using a quality-based one, or one in which the teacher determines grades in the course by their own judgements of quality of student performances. Those judgements allegedly are an accurate enough measure of the standard for writing or communication set by the program through their SLOs. In short, using a labor-based grading system can mean not teaching to standards or outcomes established by a program or school. The result is that students do not learn what the course is meant to provide them.

But there is a hidden problem concerning judgement in this logic. And we gotta talk about it before we can even get to understanding SLOs. The two concerns are connected.

The problem is a classic one in psychological measurement. Can any teacher measure something like SLOs in their students' performances the same way as other teachers will in the same school or department? Additionally, can any single teacher measure their own students' literacy performances the same way every time? Can teachers be consistent in their grading of quality writing in classrooms? If you have a standard, and you say you use it to evaluate student performances, you better be consistent, or you'll be unfair to your students. These are questions of reliability.

What the research shows is that we teachers of writing, like everyone else, are not that reliable when it comes to evaluating literacy performances, no matter the standard used. This is how human judgement and literacy work together. It's also paradoxically why it's a good idea to get lots of responses or feedback on your writing before you finish it. The more people who give you feedback, the more kinds of judgements you'll get, and this means, you'll have richer and more valuable information to make changes. But in a situation where grades and evaluations mean granting or withholding opportunities from students, then this unreliability or inconsistency in how people evaluate language is a problem of fairness. It's also a problem of learning too, since why would any smart or savvy student listen to their peers' feedback when the teacher is the only one grading their final drafts?

How much did teachers agree? In this case, squaring .41 turns out to be .1681 -- that's just under 17%. So what these researchers found was that when they gave the same 300 papers to 10 English teachers, those readers only agreed about 17% percent of the time on grades given to all those papers, while the full set of 53 readers had even lower correlation of .31, or about 10% agreement. So, even if a group of teachers are off by a small margin in how they evaluate student performances in their classrooms, the results can be quite large in effect when measured across many students and graders. But disagreement is often quite large when it comes to language. What the Diederich, French, and Carlton study show is that agreement among readers who are not normed to each other, even when they are highly specialized and trained in a discipline, like English teachers, are quite random in their evaluations of literacy.

Few Schools, Departments, or Programs Assess Their SLOs

The above problems with the reliability of teacher judgement makes the use of SLOs -- which demands that judgements in classrooms be uniform and consistent if those classrooms are fair and accurate -- dubious and dangerous. I've yet to meet a college writing program, or a high school English department that had installed processes that could reasonably assure that the SLOs they have for their courses are measured reliably. And I'm putting aside the problems with where those SLOs come from, who they privilege, and who they harm. I'm simply talking about using them responsibly and ethically in the ways we say we use them. Usually, from what I can tell, programs use SLOs to say they are doing their job, but having SLOs and assessing them are very different things. The first is easy to do and means very little. The second is very hard to do and very expensive.

|

| Photo by Sandy Duncan Rudd, "Future Uncertain" |

If a school or classroom is gonna use SLOs to say they are holding students to particular standards of language, then they better have formalized ways to validate whatever decisions they make from classroom grades of writing quality. What does this mean? It means, you need a number of things outside that classroom to assure that what's happening in it is fair. Below is one of the simplest sets of requirements I can think of, and it should illustrate why such procedures are not done in most schools and how costly and time-intensive they are.

- a set of three outside readers (outside of each classroom) who are also teachers or know the curricula and discipline well will read and grade a significant sample of student writing

- a number of norming sessions for those outside readers will occur before the readings happen

- statistical analyses run on the grades given by the outside readers and the grades from the teacher of record (this will produce the correlations)

- a process of getting teachers together to discuss and make any curricular and teaching changes to their classrooms, assignments, etc.

Without some version of the above assessment elements happening regularly, the use of SLOs is very dangerous. Why? Beyond the unreliable or inconsistent grades and outcomes that likely will occur in a system that is predicated on the opposite, SLOs end up hurting particular groups of students for no good reason. The students are whom you'd expect: students of color, multilingual, and those students who do not come to the classroom already using the language standards and habits in the SLOs. SLOs create a funnel and filter of opportunity, one takes a large group of diverse people and rewards a few of them. A few make it through the funnel and filter. This is how white language supremacy operates.

The White Supremacy of SLOs

But we can also argue against the very idea of SLOs by looking at where they come from, who is in charge of judging for them in student performances, what their training is, who benefits, and who is likely disenfranchised from all these patterns. And there are patterns, ones you likely can anticipate. These patterns are classed, raced, and gendered because our educational systems, our ways of training teachers, our classroom pedagogies, our society and all that it produces is based on a white supremacist set of assumptions, rules, and habits which reproduces such patterns in teachers and administrators.

In this case, what gets reproduced in the use of SLOs are the habits of white, middle- to upper class, monolingual English language users (see this post and this one to read more about this), which then reproduces people with just those language habits in future teachers and administrators. Just to give a quick sense of one side of this problem, here's a graph from the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) that shows the demographics of full-time college faculty in the U.S. in 2017.

Now, this represents only 1.5 million full-time teachers from across all disciplines, which are only 53% of all faculty who teach at the postsecondary level. So while these numbers will likely look different in that part-time group, and in English departments and Writing programs, my sense of visiting many writing programs and English departments over the last fifteen or twenty years is that they represent the kind of racial and gender disparities that affect who judges those SLOs in writing classrooms.

What I want you to notice is that in the instructor and lecturer categories, the groups of faculty most likely to be teaching first-year writing courses, between 76%-80% are white, more are women, and very few are black males. These are the folks who teach writing in college, and it should include all those part-time faculty not in the above graph and graduate teaching assistants but it doesn't. I've visited 36 different college and university writing programs and English departments in just the last two and a half years for various reasons, without exception, their writing teachers are predominantly white and female. Their grad students are the same. The above graph likely doesn't look that different if you included all those who teach writing courses in college. In fact, it very well may be even more skewed toward white teachers.

Of course, being white and female ain't a bad thing and it doesn't tell us one's linguistic proclivities, but it does suggest patterns that are real. It also suggests a few things about one's relationship to language and to the educational structures in the U.S., things beyond good intentions and ideals of fairness to all. How do you think one gets the privilege of being a writing teacher, even a graduate teaching assistant? You demonstrate the habits of language and judgement that are common in the discipline, in academia, and in the groups who established those places, namely white, middle- to upper-class, monolingual English speaking men. This means that no matter how wonderfully stated your SLOs are, they likely will be used as a white supremacist tool. It's how the system works. It's unfair to a significant number of students.

Grades vs. SLOs

Oxnard College offers a clear explanation of SLOs verses grades, which illustrates both the attraction to SLOs by departments and programs and the problem I'm describing above.

As the webpage above states, grades are not SLOs. This means that using quality-based grades does not mean you are following or even administering SLOs. It means you are grading by a standard you've set. They call it an "objective" and it's essentially one step removed from the learning that any course or teacher is attempting to teach or assess.

In fact, grades often are a problem in classrooms that are dictated by SLOs. As the Oxnard page tries to make clear, teachers get confused between grades and SLOs. That is, when a teacher uses grades of quality, they often can be fooled into thinking that they are measuring outcomes, but that is not necessarily the case. And since SLOs and grades are not the same things, a teacher can be using SLOs in their classroom, but grading students based on their own privatized objectives (that likely are not fully clear to the teacher). So if you care about SLOs, then you should be more inclined to get rid of the confusing practice of grades.

The easiest way to understand this distinction between grades and SLOs is to think of grades as a teacher's objectives and these objectives are measured typically by a number or grade. SLOs are outcomes, or the products of learning in a system or course understood or seen in students' performances. So SLOs tend to be quite specific actions or products, much more so than objectives, since objectives are actually subjective -- they are the teacher's understanding or judgement of the results they (think they) see in a group of students. Grades as objectives are like the teacher's translation of the essay that they read. Grades ain't the essay, but what the teachers thinks of the essay. SLOs are the student's essay.

And because there are many paths to any final course grade, grades are not compatible with SLOs if those grades are mean to be some measure of SLOs. So my first concern about the unreliability of individual teachers is often what makes grades so problematic. In short, grades are a horrible measure of course or programmatic effectiveness, especially if SLOs are used to define such terms. And SLOs, because they are more specific and require very particular products to be demonstrated in student performances -- think the funnel and filter -- they too are a problem. They are white supremacist.

WPA Outcomes Statement and White Supremacy

SLOs embrace white habits of language and judgement in how they get used, or how they have to be used by default in classrooms. Remember who gets to be writing and English teachers, where they come from, and what they must demonstrate in order to be teachers. Who do you think creates the SLOs for any course or program? Cycles of reproduction.

The most commonly used outcomes for writing programs in colleges and universities is the WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition. Developed by a distinguished group of writing researchers working under the auspices of the Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA), it was first published in 1999 and has been revised two times since then. Its most current version was updated in 2014. Many programs use the Outcomes Statement either as their writing program outcomes or as a starting place to develop their own. I'll offer just one example from the Outcomes Statement to illustrate how such a document has a hard time escaping the white supremacist outcomes it inevitably reproduces, even when good, smart, ethical people use them.

Here's one set of outcomes from the first-year writing program at my institution, ASU. While I'm not a member of that department or program, I know everyone. The web page that offers their program goals references the WPA Outcomes Statement and clearly it has influenced their SLOs. Rhetorical knowledge is the goal, and what that means in terms of outcomes that students will do is listed below it.

Now, there is nothing inherently wrong with these SLOs. I don't find their articulation to be white supremacist. It is in how they are judged and used in classrooms that makes them so. If writing teachers come from mostly white, middle- to upper-class, monolingual English speaking places, and they require such habits of language to be bestowed the privilege of teaching writing at a school, then how do we think something like "use heuristics to analyze places, histories, and cultures" will be understood, seen, and evaluated in a writing course? It's up to the teacher to decide what exactly this slippery outcome actually looks like. The funnel and filter is still in place, even if you don't use grades.

How teachers understand what these outcomes look like in student performances is crucial to the maintenance of white language supremacy. And most of the time, teachers do not realize they are participating in white language supremacy. In fact, the reproduction of white language supremacy requires that teachers NOT realize they are doing it. If they did, most would stop and do something else.

There is a lot more to talk about. I could go through the WPA Outcomes or any set and discuss the ways white habits of language both influence those outcomes or how teachers must use them from their own white habits of language and judgement, but I'll hold off here. I'll say that judgements that lead to grades usually are the key to white language supremacy.

I'll end by saying that SLOs and grading often work together to produce white language supremacy, and unfairness in classrooms. There are good things to see in SLOs, but lots of bad stuff too. Labor-based grading contracts do not solve all of these problems, but they do make for a classroom ecology without grades, and they offer students a choice to be funneled and filtered, or not. I think, that is important in producing a fair enough classroom ecology.

Comments

Post a Comment