Blogbook -- Chapter 1: Race As An Organizing Principle

Entry 4 (Mon, 01 Mar 2021)

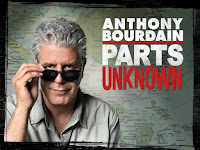

Race organizes how we understand people, their languaging, and our histories. Take for instance any travel book or travel show, which if done right should arguably be what we might call “multicultural,” a show that values a multitude of cultures, places, people, and languages. That is, traveling around the world to learn about different people, places, cultures, and foods seems like a project that values and respects a wide array of people and places.

But how is such traveling, places, people, and languages organized for consumption by a viewing audience? And I use that term, “consumption,” consciously since our society mostly produces things for consumption only, even education. Who is that audience imagined to be? What are their dispositions toward things? How might such a show or book be a racial project, one that does race making, or even produces racist outcomes?

At its face, a show like the late Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown would not be Eurocentric. It wouldn’t be racist either. But how does race influence the way the show, and all the other shows just like it, organize itself, even if tacitly? Who is the traveller and how are they racially identified? What is framed as exotic and noteworthy of learning about by the traveler, and by extension the audience? How is difference created for the audience -- that is, how is difference placed in opposition to the audience in order to be recognized as different from the audience? In short, how is race functioning to organize the show and by extension the audience. |

| Chef Marcus Samuelsson |

Brave WorkWrite for 5 minutes. Do our classrooms and discussions of “diverse texts” orient themselves in similar ways as travel shows? How does race actually organize your readings and lesson plans in your classrooms, even if you are not consciously thinking in racial terms, in fact, especially when you are not thinking about race?

|

| Chef Mashama Bailey |

|

| Chef Christine Ha |

I wonder how those two Moroccan women would answer Bourdain’s questions about their country? But wait, that ain’t the point. The White racial perspective of Morocco is what makes the show what it is, not a native perspective. The two Moroccan women serving are just scenery. They are there to make the dining scene authentically Moroccan, otherwise it’s just some White people eating at a table together.

Bourdain references several times in different conversations in the episode his childhood heroes, Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs, famous expatriates who lived conspicuously in Morocco. It’s from these White expatriates and Bourdain that most of the show’s ideas about Morocco are voiced. No actual Moroccan gets much screen time to represent their country or city, or really even themselves. They don’t voice the interesting histories or ideas. That’s Bourdain’s job. He’s the authority on this place apparently, enacting a long tradition of the White European authority on the Orient, something Edward Said explains thoroughly in his book, Orientalism.

While offering a passing reference to it in his introduction, Bourdain nevertheless rehearses Orientalism, a White supremacist discourse that silences Arabs, Muslims, and others of the Middle East, while holding up the White expert, who is in this case the White world traveller. Said’s explanation of Orientalism is important in understanding race and racism in this show, so I’ll come back to him later in this blogchapter (note 11).Often in the show’s episodes, what makes such locations exotic and interesting are their histories of Black and Brown racial violence and tragedy. These histories make such locations interesting and worth traveling to, particularly by White world travellers. Like Bourdain, the imagined White traveler might experience such violent and tragic histories vicariously, then sample new cuisine and go home, retreat back to safe White places, places made from the violence and wreckage of previously colonized and mined Brown and Black places (yes, I’m speaking of the U.S. too). I’m thinking of his episodes on South Africa, Libya, Congo, and Vietnam.

The facts Bourdain gives are about wars, strife, the LA race riots, and government coops, things a distant White authority can talk about, then move on to the interesting food in front of him. The show is about him, the White traveler who learns stuff and becomes better, more enriched because of it. The show isn’t actually about the locations. If it were, there would be little need for Bourdain. The show is about the White Bourdain in those locations. How does Bourdain’s show help the extreme poverty in Columbia, or the violence in Beirut or Myanmar?

And what of his White audience? They learn some superficial things and are apparently enriched too by finding out about different places and faraway people, but not engaging with anything, anyone, or any actual history that may impact their lives. Nothing has really been done. This is what racial organizing in White supremacist societies do. It upholds the White supremacy, upholds Bourain’s expertise and his ability, his privilege, to move back and forth from one interesting place to another, taking along his White audience.

Seeing how race tacitly organizes such shows should make us question the ease that White authorities like Bourdain have to cross borders, move in and out of a variety of spaces, while racialized others, the Black and Brown bodies around him, do not have such ease. In fact, they appear to be trapped there. They are fixed on a racial landscape for the White traveller to explore.

One measure of the racial organizing of Bourdain’s show is to consider all the places he travels to in the 93 episodes of the twelve seasons the show ran. If broken down into geographic categories (i.e. Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Africa, Middle East, and Carribean), most episodes are situated in Asia (20 episodes) and North America (23 episodes). The next closest geographic location is Africa (10 episodes). The majority of the mostly U.S.-based locations in the North American category are represented as ethnic locations, which get racialized in the show’s travels, food, and lessons offered to the audience. These are places like: Korea Town (LA), New Mexico, Detroit, Mississippi, Miami, Charleston, Chicago, Queens, and the like. They are parts unknown to White middle class people, by and large. That’s what makes them unknown, and travel-worthy -- the dark, exotic next door, just over there. This is racial organizing, even as Bourdain is respectful of the people, places, and customs he encounters. But respectfulness and good intentions ain’t enough in a White supremacist travel show world.

Now, I don’t mean to pick on Bourdain’s show or him. There are lots of things to admire about him and his show. But his travel shows are extremely popular and arguably define the genre today. Most follow his lead. A quick glance at a listing of current and past travel shows reveals the same racialized framing. Most use White men traveling around experiencing far away places -- again, far away from their White places.

Two centuries earlier, we might have called these White men “explorers” or “conquerors.” Today, we call them celebrities. But they function to make race in the world in the same ways. And the result is that they and their shows orient the rest of us in racially White ways, particularly to texts, and language, and bodies, and food, and locations, and even ourselves.

Brave Work

Study and write for 60 minutes.

Watch an episode of a travel show, perhaps one you enjoy. As you watch, pause the show at least 4-5 times, maybe every 5-10 minutes, and write.

How does the show frame its narrative and narrator? Where is the episode situated? Why there? Is it marked as exotic or far away? What are the markers? Who is the narrator or host that you follow around and how is he/she situated in the place travelled to (as an adventurer, learner, newbie, innocent, authority, etc.)?

How does the show frame its ideal viewer? What are you as the viewer supposed to notice, learn, appreciate, etc.? In what ways does the show help you identify with the host? Do you share the same racial, gendered, and socioeconomic positioning that is assumed of the host? Do you use the same kind of English as the host? How is the host’s subject position referenced (if at all) in the show?

The imaginary audience that is conjured by these shows is framed as White subjects, with conventional habits and dispositions of Whiteness, even for those who do not identify racially as White (I’ll discuss habits of White language, HOWL, in blogchapter 2). It’s important to understand that Whiteness in the way I’m speaking of it here, while historically connected to White people and their practices and habits, does not designate White racial people always. It references a subjectivity, or a subject position, that is created in the system of media, travel shows, literatures, languages, and the society in which those things circulate. It’s part of the way racial formations are created and recreated.

Whiteness can be a perspective or positioning relative to other raced objects, activities, places, behaviors, clothing, and people. It can also be language, accent, and the like. Audiences are meant to accept or take on the habits that characterize this White subjectivity in order to understand and consume the show, to accept it on its own terms. This means a middle class Black viewer can take on those same White habits that the show offers, even though in society that Black viewer may not receive all the benefits that the White habits might confer onto someone who is identified with other White racial markers.

White racial habits constitute an orientation to the world, its peoples, and languages. Since we all live and operate in commercial media systems that are dominated by Whiteness, we all usually get interpellated or hailed as White viewers, and take on the habits offered in shows like Bourdain’s. It’s the orientation that is usually available to us. Interpellation is important to understanding the racial framing of such shows and literature.

Interpellation is a term that Louis Althusser used to describe the way our world is structurally set up to make individuals into subjects. Subjects already exist in the system, so that easy meaning can be made. Individuals do not. It is not easy to make new meaning each time we interact with a new individual. For instance, the abstract categories of the subjects “man” and “woman” carry with them meanings, social boundaries and expectations that we use to communicate and make sense of the world and those in it. We know how to act around another person once we’ve identified them as man or woman. This is why it becomes more confusing for many when they meet someone who resists such gender binary categories. The individual dresses in contradictory ways, or does not act or speak in ways that seem to correspond with other markers perceived. What the individual is doing is resisting the interpellation of the male-female categories.

So to be interpellated or hailed as a White audience member of Parts Unknown means that you take on the subject of a White viewer and respond in ways that are already created and reaffirmed in the system and show. The most obvious example of the way shows do this hailing is through laugh tracks on sitcoms. We are to laugh with the fake audience we hear. Through such subtle ways, the Parts Unknown creates the ideal viewer as White in the ways that Bourdain embodies. This includes biases, common responses, dispositions, likes, dislikes, preferences, reactions, etc. Althusser explains it this way, “all ideology hails or interpellates concrete individuals as concrete subjects, by the functioning of the category of the subject” (note 12). Ideology in this case is the category of Whiteness as a subject watching the show, and to be more specific, it is a White masculine-oriented subject. This subject is also recognized as the traveler worth watching and listening to.

Thus, "the exotic" in the show means places in the world that are unknown to the White, European and American perspective or subject position. An explorer and world traveller worth following is an enlightened White man who speaks an English suited to such a body. While viewers may not recognize this racial organizing of the show, or how the show frames what information the viewer takes in and what lessons are learned (and what to do with them), it is still operating, affecting us all. The show participates in the southern language strategy. It implicitly makes race. Race is ubiquitous.

The bottom line is: We don’t get to escape race even when we understand it isn’t a biological or scientific concept, even as we understand that it is often harmful when invoked or ignored. This means that to say you “don’t see race” is dishonest, or at best, irresponsibly and willfully ignorant. Since ignoring race is equally, if not more, damaging and hurtful than using race to stereotype people or rank their worth. Ignoring or denying race in the world ignores or denies the real ways that race is a socially constructed concept that has political power to organize people and their ideas. It ignores the ways it organizes our world and has real material effects on people, ignores how it still operates, still influences, still works in our languaging and ways of understanding. If we ignore race, we ignore a good part of the ways we are all interpellated, or hailed as subjects.

Because the concept of race has been so influential in our histories and in the ways our world is made, we are obligated to understand the history of race. We need to talk about it as it relates to the topics, subjects, languages, and literatures we present to students. And this is especially true in classrooms where literacies and language are either the topic of learning or the mode by which learning happens. Usually, both happen simultaneously.

Furthermore, language is an integral part of our social world. And just like Said’s Orientalism, to say that race is a socially constructed idea is also to say that it is constructed with words and other social behaviors and practices. We use these behaviors and practices in classrooms to discuss, understand, and make sense of everything. We all make race everyday in our words, or by their conspicuous absence. Bourdain, like so much else around us, helps form our racialized notions of the world as much as any theorist, scientist, teacher, or politician. Race may not be scientifically real, but it is socially real. It organizes us, our language, and our own subjectivities.

---

This blogbook is offered for free in order to engage language and literacy teachers of all levels in antiracist work and dialogue. The hope is that it will help raise enough money to do more substantial and ongoing antiracist work by funding the Asao and Kelly Inoue Antiracist Teaching Endowment, housed at Oregon State University. Please consider donating as much as you can to the endowment. Thank you for your help and engagement.

Comments

Post a Comment