Blogbook -- Chapter 1: Racist Discourse . . . And The Case of the Irish

Entry 9

Derald Wing Sue, Professor of counseling psychology at Columbia University, explains that racism is institutional and operates through “standard operating procedures (SOPs), which represent the rules, habits, procedures, and structures of organizations that oppress persons of color while favoring Whites” (note 60). The bottom line is, racism is the norm in society because it’s structural. It’s everywhere. It ain’t no anomaly. It happens because the system is working the way it is designed to, not because something or someone went wrong.

Recently, I found a great set of tweets from @Absurdistwords that captures the ubiquitous and structural way racism and White supremacy exist in the world. And while we can laugh at the connection to high fructose corn syrup, the simile is pretty accurate.

So to be antiracist ELA teachers, we need to understand the history and nature of racist discourse, which is more than just understanding that racism is a discourse. We have to understand the workings of racist discourse. We need to be prepared to teach in abnormal ways against its workings. We should be able to create and engage in nonstandard operating procedures, work with our students against, or in spite of, the discourse that makes us, our classrooms, and our curricula racist by default.

One way to think about racist discourse is to think of it as a field or a system itself that is a part of other systems in society. What do I mean by a “field” or system? I mean, as the previous section (and posts) illustrates, racism is material, structural, and historical, while at the same time people participate in it through language, symbols, behaviors, and actions, even when our actions and language are not explicitly prejudiced or bigotted. This means that we are surrounded by racism through societal structures, institutional policies, disciplinary or professional training, and practices, all of which require language to operate as much as they require other things.

Therefore, we should keep in mind that everyone participates in racism, no matter our intentions or beliefs, or even the racialized subject position others perceive or that we most identify with. Our own subject positions or expressed ethics do not determine whether we have participated in racism or racist outcomes around us in schools. We have. This is a given. Remember, racism is the structural norm. It happens when things go as planned, when systems and policies work the way they are designed. Now, this does not make our teaching, school work, and their effects in the classroom hopelessly racist. It does make, however, more careful work, more self-conscious anti-institutional work, if we want to be antiracist.

Brave Work

Write for 10 minutes.

Think about a typical classroom activity or practice that you do. Maybe it’s how you read student papers, or grade them, or the rubric dimensions you use, or your expectations of writing, the ones that seem self-evident and unarguable. Or maybe consider how you conduct class discussions, how you set them up, call on students, ask for participation, etc.

Describe the standard operating procedures (SOP) in this practice or activity. Now, consider them deeply and invisibly racist, producing some kind of racist outcome. What are the typical results in each identifiable racial formation in your classroom? When you look carefully, do White students act differently, perform differently, than BIPOC? You can also ask this question intersectionally. Do Latina or Black women act differently? How might their be racist biases in your SOPs that frame and create uneven outcomes in students?

This structural understanding of racism isn’t new. The structural has been attached to the word “racism” since it was first coined. The German Jewish sexologist and physician, Magnus Hirschfeld coined the term late in his life in his posthumously published book, Rassismus (Racism, 1938). The book is a study of the racism he saw and experienced at the hands of the Nazi regime in Germany. Hirschfeld argued that Nazi racism was not new, nor was it an aberation in Western society. He linked racism back to the race pseudo-science of the German Enlightenment, back to Blumenbach and others, and to German colonial projects. Essentially, he argued that the societal and ideological structures in the world were fertile grounds for racism. Racism, he argues, is structured into Western societies (note 61).

As Joe Feagin and Sean Elias explain, Hirschfeld’s term was not primarily about individual bias or prejudice. It was structural: “‘racism’ meant far more than racial bias, for it involved a broad racist framing with a developed racist ideology closely coupled with well-institutionalized discriminatory practices, including institutionalized structures for elimination of racial groups” (note 62).

Racism, as coined by Hirschfeld, started out by referring to racial bias within and because of institutional frames, structures, and practices. And so, the term has always been a term about structures and systems, not just individuals behaving badly. Individuals behaving badly most often do so because systems around them, structures that create them and their choices, make such behavior conceivable and possible. Racist structures and practices encourage and make possible racism. In fact, they tend to define it as preferable and ethical.

This explains lynching and racist discourse of the south, Nazi racist discourse and Jewish genocide, and the U.S. government’s ongoing genocidal settler colonial violence and theft of indigenous lands justified as “manifest destiny” (note 63). Those whom we might call racist are not the root cause of racism, but an effect or product of larger racist systems. While we may have to overcome or confront people acting or making racist decisions in front of us, our primary antiracist goals should be to dismantle racism, the system.

Recall Omi and Winant’s racial formation theory. They say that in society race evolves. It forms and reforms through numerous and ongoing racial projects. Not all racial projects are racist, but all work to define and redefine race in some way. To be racist, according to Omi and Winant, a racial project has to “creat[e] or reproduc[e] structures of domination based on racial significations and identities.” That is, racial projects create the way people represent race and identify (or get identified) with such ideas.

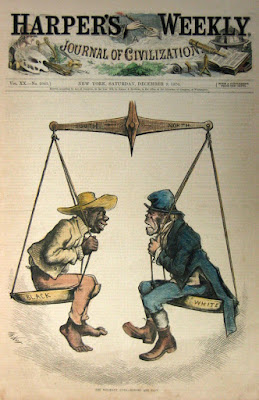

As an example, consider the Irish in much of the nineteenth century in the U.S. Racial projects made mid-nineteenth century Irish immigrants not yet White. At the time, they were constantly referred to in similar terms as Black Americans, as dark, lazy, uncivilized, impulsive, and semian, or as “a ‘savage mob,’ a ‘pack of savages,’ ‘savage foes,’ ‘demons,’ and ‘incarnate devils’” (note 64). And to make the comparison clear, the Irish were also referred to as “White niggers” (note 65). This comparison, a kind of categorizing, is obvious in political cartoons of the mid-century, as seen in Figure 3 from Thomas Nast, a German-born American political cartoonist popular at the time.

But as Noel Ignatiev explains in his study of the Irish in the U.S., by the end of the first decades of the twentieth century, the Irish were racially White in the U.S. polity (note 66). These racial projects, such as the one that the Nast cartoon participates in, led to or reproduced structures of domination in society through ranked characterizations of race. Domination is an outcome of uneven or unequal power relations in a system or society that racial projects make. Unequal power relations come from systems that make hierarchical categories, or taxonomies, that are ranked in some order of importance, value, beauty, or preference.Often, the problem is that when you’re in a system of uneven power relations, it is hard to see those relations as unfair if you are in positions of more power and privilege -- that is, if you’ve benefited in and from the system. It’s easy to think, “I haven’t had it easy; I’ve worked hard for what I have, and I made it; why can’t they?” The “they” is anyone who is marked in the system as not meritorious, not working hard enough, not good enough. When we look at the numbers, the patterns of those who are not meritorious are always racialized as non-dominant in U.S. society. That is, they are too often not racially White. Today, similar kinds of racist discourse make our school systems favor middle and upper class White students at the cost of Black, Brown, and working class students.

It’s easy to assume that fairness in our society or classroom is a zero-sum game. Either you work hard and get rewarded or you don’t. It’s easier and often preferable to assume that how students are rewarded in school is a product of how hard they’ve worked or not. This assumes that systems do not grant privileges automatically. It assumes that everyone starts in the same place and in the same ways in our classrooms. To believe that everyone has the same hard life, or that everyone’s hard work equals the same kinds of successes and opportunities, to believe that those who lack success or opportunity are to blame for their own misfortunes, is to ignore the different degrees of hardship and access to opportunities and privileges that exist in our uneven systems and society. It minimizes racism and White supremacy. It hides the unevenness in life and society. It ignores the very real racist discourse that is everyone’s SOPs.

---

This blogbook is offered for free in order to engage language and literacy teachers of all levels in antiracist work and dialogue. The hope is that it will help raise enough money to do more substantial and ongoing antiracist work by funding the Asao and Kelly Inoue Antiracist Teaching Endowment, housed at Oregon State University. Read more about the endowment on my endowment page. Please consider donating as much as you can to the endowment. Thank you for your help and engagement.

Comments

Post a Comment