Blogbook -- The Affordances of Racist Discourse in Literacy Classrooms

Entry 18

Let me summarize what I’ve been discussing in the last four entries of this blogbook (entries 14, 15, 16, and 17). I’ve been asking us to think of racism in our classrooms, texts, language practices, and world as a discourse. But the idea of what “racist discourse” means is bigger than just words. Racist discourse is both material and linguistic. It’s actions and decisions, and it’s language and stories that we use to explain and talk about those actions and decisions. Marxian dialectic and hegemony, as well as verum-factum and verum-certum that explain Vicovian common sense, help describe how we often consent to our own oppressions, that is, consent to racist discourse as the dominant set of conditions we all live and participate in, regardless of our better intentions or ethical stances on things.

Our consent to hegemony usually comes as “preferable systemically-constructed consciousness” -- that is, consciousness that is created in the system as preferable -- defined as preferable or appropriate or even “natural” -- and often rewarded. We think free and unregulated markets are good for the average laborer or citizen, but they never have been. They’ve mostly been good for Capitalists, those who own companies and corporations, because it means an economic playground with no rules, or rules they make, and no one policing corporate misbehavior but the corporations themselves. Meanwhile most people circulate attractive and soothing stories about how Capitalism is good for average folx because it provides the grounds for innovation, healthy competition in all marketplaces, and even personal freedom, choice, and success -- you too can be a rich Capitalist! These messages are preferable systematically-constructed consciousness.

The same critique can be made of anti-Black racism in policing and the legal system. Many accept the idea that the police are just doing their jobs, not working in structurally racist organizations that create criminality out of Blackness. Many prefer to believe that the U.S. legal system is not slanted against Black citizens, that the higher incarceration and sentencing rates of Black defendants than all other racialized groups are products of fair systems of justice.

Why do we think these things? Racist discourse that makes up the bones of everything around us, and confers benefits to White people, even though those benefits are not evenly distributed when we account for socioeconomic status and geography, among other social dimensions intersecting in White racial formations. But our stories are soothing. Ain’t it more comforting to believe that the systems in place to protect you, to educate your kids, and to make justice and fairness happen in your world are NOT racist, are not unfair, are not White supremacist because, well, you have not experienced such unfairness and systemic punishments? It’s easier to sleep at night with that idea, less so with the idea that we live in White supremacist conditions that make us in important ways.

Teachers and school administrators too see things such as singular elite White habits of English, rubrics and standards for all classrooms, and learning outcomes as preferable because they match the ideas that the system of schooling has planted in those teachers and administrators. Teachers and administrators benefit from such habits of language as standards and the stories about those standards’ neutrality, racelessness, and goodness for everyone. We may have different relations to those English language standards, given who each of us are, where we come from, and where we sit in the system, but deep down, the hegemony of the system constrains all of our choices and ways of recognizing what “good writing” can be.One trick in our conditions is that our own individual recognition of such goodness in language feels like an exercise of agency. It feels like a choice we make. We aren’t being forced to believe or think things. Instead, we consent to it all, often with little or no recognition that many of our decisions have been slipped into our back pockets throughout our lives. And now our pockets are full of what we take as the stuff we made and chose. Our consent is a comfortable life-long practice, a long set of small decisions, actions, and habits that amount to our slow acquiescence to the racist status quo around us.

We turn around one day as a writing or English teacher, principal, or writing program administrator, and the good we can recognize in languaging is made of the White habits of English language, the same habits found in those that schools and colleges promote as singular standards of “good writing.” We recognize ourselves in those standards, and one consequence of this is that we have a hard time recognizing other habits of English languaging as good writing, critical thinking, or effective communication.

Interpellation identifies the process by which individuals take on their own identities from the stuff around them, and of course, take on all that goes with those identities. Each identity, or each category of a subject made possible in our material conditions, have predefined aspects to them, which includes norms or expectations of languaging, behaviors, and other habits. These aspects of each category are never even or exactly the same in any two individuals, but they do not need to be in order to be taken as that particular category of a subject.

Althusser says, “all ideology hails or interpellates concrete individuals as concrete subjects, by the functioning of the category of the subject” (note 111). What he means is that our language and other structures that make up our material conditions have in them assumed categories of subjects, sort of like predefined sets of ideas about what certain kinds of persons or subjects are, or what subjects are possible to recognize in the world.The categories of man and woman are an easy example. You know what these subjects are even without any further details. You even know how to generally act toward each, and those relations are different for each category of the subject. The same can be said of the categories of subjects of Black, White, Asian, Latine, etc. But of course, these categories do not account for nonbinary people or multi-racial or multi-ethnic folx.

Althusser says that we come to recognize ourselves as one or more of these subjects only because they already exist in our conditions. So interpellation is a hail, such as a “hey you” on the street, because when you answer that hail by turning around or saying “what?” you recognize automatically that you are a subject being hailed -- that the “hey you” is directed at you, a subject. Thus as Althusser says, we are subjects because we are subjected to ideology, or the material conditions around us -- racist hegemony -- that already have predefined categories of the subject that we have accepted through our own responses.

Our choices of subjects are often limited, though, because not all kinds of subjects are accountable, or fit into, the present systems easily. They cause confusion and trouble for meaning making. For instance, our world usually presents us with only two gender options, and slowly, continually, in a multitude of ways before we ever realize it, we have been interpellated as a “boy” or a “girl,” and we take on the characteristics that the subject category implies that we’ve come to recognize as who we are. We have been interpellated, and we were a part of that life-long process. It all seems like mostly our own exercising of agency. And it is and it isn’t.

Of course, this is part of the problem of interpellation in a world that doesn’t present all that is possible for us to be or identify as. What we get is a selection of what is possible, a constrained or bounded set of options based on what the systems, or our conditions, determine is the range of possibilities in any given context. Our choices, then, are always ones that sustain the system in place, because they are made from those systems. The acceptable choices we have rarely make the system unstable. This why many people have trouble with understanding or accepting nonbinary folx. It’s not simply that their presence is confusing, but that their presence makes the system that some use to understand and make sense of their world unstable. The same criticism can be made of singular White standards of English language in all classrooms.

For instance in our classrooms, our notions of appropriate language expression, of standards of English language, have the same kinds of stock categories of subjects embedded in them. These standards limit the kinds of subjects our students can take on through language in our classrooms when those standards are used to do things like grade or determine progress and proficiency. But teachers also use versions of them out of necessity in their own habits of language and judgement. The primary subject in such standards, the central category of the student-writer subject, is a middle- or upper-class, monolingual, White person (note 112).

Language interpellates us into subjects heard by others and by ourselves, so when BIPOC students do not match up with the categories of subjects that constitute the White standards of English language expect of them in school, then they are judged as deficient, unprepared, not ready, or in need of remediation. Why? Because the subject positions BIPOC often can take on in languaging are not well accommodated in the White standard of languaging expected in school, the one embodied in the teacher and their habits of language, and the one in the rubric or learning outcomes.

Now, I’m not saying that BIPOC students are unable to learn White standards or habits of English languaging. Of course, we are. I’m a good example of this. I’m saying that those who judge, teachers, because of the history of the way that judging happens in classrooms, because of the way teachers are interpellated as Whitely teachers with White habits of language in their back pockets, and because of the categories of the racialized subjects of "good" student-writers embedded in standardized English, it is not usually possible for many -- maybe most -- BIPOC students to be read as, to be judged as, a Whitely student-writer. These categories are contradictory in schools because of singular, White standards imposed on everyone.

So Althusser shows us why we all participate in such racism in our classrooms, explaining why over time we can come to be thoroughly interpellated as writing-teacher-subjects who have made themselves out of the White supremacist stuff of the world and their disciplines through a long set of small decisions, actions, and habits that amount to a slow acquiescence to the racist hegemony around us. There is no better set of habits to consider in this interpellating process than White habits of language that make for White language supremacy in standards and judgement practices.

And so, one lesson that Althusser teaches us is not that we have a predefined, limited array of subject positions we can inhabit -- this we likely already know. His lesson is that our world, our conditions, move us to accept whatever category of the subject we already identify as in such a way that it is not clear when or how we made that decision. It’s a lesson about what the nature of agency really is, how we don’t fully control that agency, how agency itself should not be defined primarily by how much control a student or teacher has over their decisions or the categories of subjects they are taken for or read in others in classrooms. And our choices about language, both ours and what we identify as preferable or acceptable in our classrooms, are a part of the categories of the subject possible in our material conditions, which includes again our languaging and the standards we often imposed on students.

A Hypothetical Example of How We Read with RacismYou give students a day or two to write it and you collect the paragraphs and read them. You get the two hypothetical responses below from two different students. We’ll put aside for the moment the flesh-and-blood students whom you would actually know already, so you’d come to each response with some expectations and past history of readings that are different. But let’s keep this simple since I’m just trying to illustrate how interpellation generally affects our judgements of student writing. Now a teacher might question more deeply the materials of the categories of subjects they assume when they read student writing in order to judge it.

Student 1. Reading it when I read a book. I mean it be understanding words on a page or somewhere else and this how people communicate with each other. It be like me telling stories that ain’t real but seem real because I read the words the words seem to disappear and then they just the people and what they do in my mind. Reading it be an amazing thing cause it a human act. It be talking and storying with each other.

Student 2. Reading is the practice of translating written language into meaning. When someone reads, they can create things, ideas, or understandings about their world. And yet, this practice is more than simply translating words into meaning. Often reading is a process of understanding what a text doesn’t say or implies because of how the author discusses or writes the text, or because of the context the text is in. For example, if I read about the U.S. Capital today, I would probably think about the siege on the Capital by protesters in January, 2021. This would surely affect what I think the text is saying. Reading is a mysterious practice that creates meaning so that we understand our world better.

In the words of David Bartholomae, both students are allegedly attempting to approximate the discourse of the academy. They are “inventing the university,” or “a branch of it, like History or Anthropology or Economics or English”(note 113). In this case, it’s English, the discourse expected in this fictitious English classroom. So in this case, part of each student’s inventing of the university is their approximating the discourse expected by the teacher, or rather the discourse the student thinks the teacher expects, which itself is an idiosyncratic version of the English language of writing classrooms -- that is, the teacher’s and each student’s expected discourse is not exactly the same, even if the teacher hands out a sample and rubric. On both sides, the expected discourse is always a construction, a reification, an imagined ideal. But let’s put that complication aside.

To be successful, the student must take on the subject position of a good student writer, one who writes and behaves as a writer in a particular set of ways, ways recognizable by the teacher as a good writer. For this inventing of the discourse to work for the student, both the student’s and teacher’s senses of what textual and other markers constitute a good writer must agree enough with each other. This situation requires that enough of the pasts of both student and teacher must coincide. They both gots to have the same kind of stuff in they back pockets. And beyond these things, we also will put aside any discussion of racial, gender, and other implicit biases that operate tacitly in all of us, which will affect a teacher’s reading of these paragraphs.

Brave Work

Write for 15 minutes.

Considering these two hypothetical examples of student writing separately. What makes for the “voice” of each paragraph? What linguistic and other choices make for the voice that you hear in your head when you read each? What disrupts that reading in each case? Why? What are you expecting as you read each sentence? What messes around with those expectations or the voice you anticipate in your head?

How do you think a person comes to acquire the voice in each paragraph? What social situations and the language used in those places might be helpful for a student to take on such a voice exhibited in each paragraph? What might they have to read and why? Which paragraph are you more sure about when it comes to what a student might need to take on that voice? Why are you more sure about what it takes to language in that way?

Now, likely student 2’s paragraph is the one you may find more value in. It's the more standardized one. If you could only give credit to one of these students, it likely would be that one, or it would be the one of these two you might use as a model to show the class. While I wouldn’t go as far as to say student 1’s paragraph wouldn’t get credit by most college writing teachers, I would say that most teachers would notice more problems with the first one, and I’m not just speaking of the instances of “its” instead of “it’s” or the missing commas and run-on sentences. I mean how it develops its discussion next to how student 2 does. In one sense, we might say, I’m speaking of the voice or subject we hear, see, and experience as we read the paragraph -- it's the voice, the category of the student-writer subject, the teacher/judge invents from the Whitely stuff in their pockets.

In our reading of these paragraphs, we might say that we assemble the student through their words, as well as our past experiences with the student in the class. Who is the subject speaking in these paragraphs? Does it match my own (as the teacher/judge) expectations of what I wanted students to do and demonstrate in the paragraph? We might even be operating from a more particular version of that question: What do I want this particular student to do or what do I hope for this student to accomplish?

From one perspective, both paragraphs accomplish essentially the same things. Both paragraphs begin with a definition of reading as a process of meaning making out of text or words. Both offer examples. And both end with a conclusion that sums up things. But there are several markers or signals in the second paragraph that identify it as written by a conventionally good-student writer, or as a demonstration of a good-student voice on the page -- and that student and voice is a White one.

The second paragraph is noticeably longer than the first. This can be a marker of what good students do. They write more, even though it is not stated in the prompt. We often equate more as better, especially in writing classrooms where the unit of exchange tends to be words. In monetary and other quantifiable Capitalist exchanges to get more is usually better. It means what you got is more valuable.

There are other signals that teachers will recognize as a part of the habits of good-student writers, the category of subject that is being used by the teacher to judge each paragraph. Signal words that function as meta-words are used in the second paragraph, which are not in the first. These meta-words identify what the discussion is about at that point, or where it is turning toward. For example, as I'm doing now, the term “for example” used by student 2 signals that the student understands they are offering an example to illustrate the previous idea. That example is also an extended one about a current event, one about the current U.S. context.

Student 2 also makes a meta move away from their original definition. They say, “And yet, this practice is more than simply translating words into meaning.” This too can be read as a marker that the student understands rhetorically that a good discussion of something like reading should turn to hidden ideas or aspects of the topic, things the reader may not see or hear at first passing. I hear this move in the construction “and yet, this practice is more than simply.” This academic move is one that looks for nuance and meaning beyond the typical or obvious. In this way, a reader may read the paragraph (and by extension its student author) as self-conscious of opening up the definition for reading, not bounding it, closing it into a one-dimensional definition.

Student 1 too makes these same moves, only without the meta-markers typical of habits of White language, the signals that tell Whitely teacher-readers that the student is conscious of making such moves, such as offering examples or opening up the definition toward nuance. The problem here is that teachers will read the second student’s paragraph as a stronger writer because that student has been more thoroughly interpellated as a “good-student writer” than the first, even though the first makes the same kinds of moves, just from a different category of subject, perhaps one we might call a Black-student writer.

For instance, the first paragraph uses some common Black English languaging. The use of the habitual “be” to indicate ongoing actions or circumstances, and the absence of the verb “to be” (zero copula) inherited from West African languages (note 114). Even the moves toward nuance, the opening up of the topic, that are marked in the second paragraph are also in the first one. They are just marked differently, marked as narrative and first-person experience. A different category of the subject is operating.

I'm thinking of the section that states: "It be like me telling stories that ain’t real but seem real because I read the words the words seem to disappear and then they just the people and what they do in my mind." This explanation is not an objectified, Whitely explanation like the second paragraph. It's a subjective, narrated one, one that uses the body of the writer/reader to explain the act of reading and the deeper things that happen in that experience. It's a transformation or process in which the words disappear from this reader and what is experienced then is "just the people and what they do in my mind." What I hear is an experiential account of reading that is not possible in the second paragraph because it uses an abstract and objectified stance, a White habit of language that assumes neutrality by disembodying ideas and ignores how one comes to know that information.

The first student is not interpellated as a standardized "good writer" as thoroughly as the second, and we know the reasons why. It is the same reasons why our own interpellations as Whitely teachers who recognize our own languaging in students’ paragraphs happen. Interpellation is a long set of small decisions, actions, and habits that amount to our slow acquiescence to the White supremacist status quo of writing and English teachers. As interpellated teachers, we take on White habits of language and judgement. Despite us saying that student 1 has the right to their Black English language, we make judgements of their languaging based on our own interpellations of them as particular kinds of deficient subjects that exist through our readings of the words they present to us.

This means also that our study of literature or language is really a study that involves racist conditions and racist language. Even when reading a text like Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between The World and Me or Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, we should be investigating the ways that racist structures around such books contribute to them, work against them, or make them in the world, even make them possible. It’s not like the New York book publishing world is clean of racism or White supremacy. It’s not like Coates or Baldwin themselves have escaped the racism of the world. And it’s not like after the publication of these books, things are now better, no more racism.

Being of racist systems is something we all must claim, even Ta-Nehisi Coates and James Baldwin. It doesn’t mean, however, that they contribute to the same degree or are positioned in society in the same ways that, say, former President Trump does and is, or Harper Lee was. But our White supremacist systems create everyone, Coates, Baldwin, Trump, and Lee. This is a lesson I’m taking from Gramsci that shows the interconnectedness and importance of both sides of this dialectic. Racist discourse and White supremacist hegemony depend on a preferable systemically-constructed consciousness about our world and what we think we see and experience. No one is immune, although some are more inoculated than others. We all fall prey to racist discourse from time to time. We must always be on guard, reflective, self-conscious. We must always look for preferable systemically-constructed consciousness in ourselves.

White Escapism

And so when we read a text with students, we are obligated to investigate the racist discourse around it and in it. The question we might pose isn’t: Is this text racist or not? The question we might start with is: How much does this text participate in racist discourse? That is, to what degree does it participate as a matter of course, since it comes out of a racist system? This includes the discourse’s material effects, history, politics, outcomes, etc. That is, we must study how the text has been used and circulated in culture and society. These things make that text too and the categories of subjects we end up being able to identify in or around them.

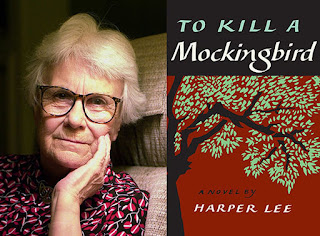

For instance, it’s significant and worth exploring with students the social outcry of the deaths of Black men such as Eric Garner and Michael Brown at the hands of police during the year or two before the publication of Coates’ Between the World and Me in 2015. Reading Coates’ book demands we know this context and how it shapes our own reading of the book a half decade later. These and other similar racial injustices surely played a role in the book’s reception in a fragile White supremacist literary world that likely felt some guilt at the time. We might read the accolades and awards the book received to be one kind of White fragile reaction by the White supremacist establishment looking to proclaim that it is not racist. There were other compelling and important books published that year. Why this one? This doesn’t detract from the power and importance of the book. On the contrary, it reveals the context and racial politics in a White supremacist society that make that book so important.Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird is also illustrative. It’s likely a book more often used in high school classrooms. The initial reviews in the South and elsewhere for the novel were praise and adulation (note 115). This was before Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his 1963 “I Have A Dream Speech,” and wrote his “Letter from A Birmingham Jail” in the same year. It’s before the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham that same year that killed four Black girls, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Carol Denise McNair.It was five years after the brutal killing of Emmitt Till on August 28, 1955 in Money, Mississippi. And it was nine years after the Cicero riots in July of 1951, where a mob of thousands of White residents stormed the apartment building where the Clark family, a Black family, had just moved in. It was an all White suburb of Chicago. The mob burned the family’s belongings, overturned police cars, and threw stones at firefighters (note 116). Everyone may have loved that book, but good ol’ fashion racism was still alive and well. It was not a thing of the past. The novel didn’t show people the error of their ways. It showed them the material context of the book’s circulation.

It’s reasonable to think that much of White America wanted to believe the half truths and easy answers to racism that Lee’s novel rests on. It’s reasonable to want to believe that racism is being solved by good White people, lawyers, everyday average people in small places like the fictional Maycomb, Alabama of the novel. Or maybe, people had Mayberry, North Carolina, on their minds, the fictional small town of the 1960-1964 TV show, The Andy Griffith Show.

Both of these fictional southern towns are places imagined by White audiences to be where good White authorities -- White men -- make the world fair and safe for everyone. Of course, they are projections of the White racial anxieties of the time. They are also racially escapist, and they make up part of the racist discourse in which Lee’s novel circulates and participates in.

The similarities between the two popular fictional small American towns seem more than coincidence. The similarities in the central White male characters also seem striking but perhaps this is only because we recognize Atticus and Andy as categories of the good-natured, White, male, authority figure subject, the preferred subject constructed in our White supremacist systems. Most White people -- and surely most White literacy teachers -- interpellate themselves as a version of Atticus or Andy.

What good White person wouldn’t want to hold tightly to the antiracist truths these fictional towns and their White authorities offer them? But as I’ve said, we don’t escape our racist history and the racist discourse that creates it. If we don’t pay close attention, break racist discourse, we’ll keep reliving it, keep remaking racist conditions over and over. The same White racial anxieties about being racist, or living in a racist world are present today. How different of a narrative is To Kill A Mockingbird and The Andy Griffith Show from more contemporary stories like Radio (2003), Freedom Writers (2007), The Blind Side (2009), The Help (2011) or Greenbook (2018)?

Equally a part of that racist discourse were the pervasive “Sundown towns” in northern and southern states, towns where Black citizens were not allowed to be in or outside after dark (note 117). Sundown towns maintained in many places all White communities, many that probably looked a lot like Mayberry and likely have changed very little today. In fact, Mayberry seems the archetype of a sundown town, having few Black characters appear at all and only one with any speaking part in all of its 248 episodes (note 118). It's all White escapism, an escape from the truth of our racist discourse.

It is not surprising from this political context and history that Lee’s novel has been (and continues to be) so popular, even granting Lee a Pulitzer Prize in 1961 -- verum-certum, a thing accomplished that proves Whites are not racist. Even Coates did not receive a Pulitzer (note 119). My guess is that today, given the visibility of racial justice movements across the U.S., we will find a rise in the use of Lee’s novel in schools.

If we assign it, we should be asking: What does this text make with the racist discourse around us now? In what ways does it participate in racist discourse? What antiracist responses and answers does it afford us today? How does it address the indiscriminate killing of Black people by police that happens so frequently today? How does it address anti-Latine racism or anti-Asian racism that occurs all the time? How can we talk back to such texts, dismantling and disrupting them and the racist discourse in and around them?

Racist discourse ain’t just about words, but it does start there. Or rather, we can start there in our classrooms. This kind of antiracist work will lead us inevitably outward to the base of our lives, to our standard operating procedures, to the facts we make, to the things we accomplish, and to the ways we are interpellated as subjects in a White supremacist world and school systems. It will lead to the ways we teach and assess, read and engage with students, and understand authors and their words. It will lead us to ways of understanding how our our pockets come to be filled with racist stuff that seems to be other things. It will lead us to ways our White supremacist world creates all of us and the things we hold dear.

This blogbook is offered for free in order to engage language and literacy teachers of all levels in antiracist work and dialogue. The hope is that it will help raise enough money to do more substantial and ongoing antiracist work by funding the Asao and Kelly Inoue Antiracist Teaching Endowment, housed at Oregon State University. Read more about the endowment on my endowment page. Please consider donating as much as you can to the endowment. Thank you for your help and engagement.

Comments

Post a Comment