Blogbook -- Antiracism Is An Orientation

Entry 21

So if we cannot have an inherently antiracist pedagogy or practice, then what can I offer you? I can offer an antiracist orientation to our work, language, and the larger schools and societal structures around and in us. We can be antiracist towards systems, not so much people. My discussion of racist discourse is from an antiracist orientation. It’s meant to illustrate one kind of antiracist orientation that an ELA teacher might take. This is why I titled this blogbook What It Means To Be An Antiracist Teacher. It’s not “how do you be an antiracist teacher,” it’s “what it means” to be one.

The how is really up to you. It is your laboring in the conditions you find yourself in among the people near you. I cannot do this laboring for you, nor can I know the important details of the how in your place with your students. You must inquire and respond to these things constantly. It’s hard work because once you figure out something, inevitably things change, and you’ve got to do something else.

When we understand the meaning and significance of our work, ourselves, and lives, then we are crafting our orientations to the world and the work we set for ourselves. Doing this in antiracist ways can offer us ways to resist the harmful preferable systemically-constructed consciousness. This is what Marxian critiques offer us, a way to understand our lives and work in meaningful ways. The critiques give us an orientation, which points us to the work we need to do in the moment with our students or colleagues.

Doing this kind of reflective work as we teach also means we have a better chance at changing things, the things that matter most in our places and classrooms. So we might say that being an antiracist teacher is about an ongoing investigation and cultivation of an antiracist orientation. This is more than a flexible strategy. It’s flexible practice because it is made from an orientation that means to dismantle racist structures in language, literature, judgement, and thought.

Now, many complain about the very word, “antiracist.” They say that it’s negative, divisive, and triggering. Why define one’s orientation by what it is against instead of what it is for. Why not have a more positive term to identify our purpose and goals, something like “socially just teacher,” or “inclusive teaching.” Kendi offers one way to see why this is less than honest in our current situation. He says,

The opposite of “racist” isn't “not racist.” It is antiracist. What's the difference? One endorses either the idea of racial hierarchy as a racist, or racial equality as an antiracist. One either believes problems are rooted in groups of people, as a racist, or locates roots of problems in power and policies, as an antiracist. One either allows certain inequalities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist. There is no in-between safe space of “not racist.” The claim of “not racist” neutrality is a mask for racism. (note 128)

In effect, the term “antiracist” does identify what a teacher is for, which is to say, an antiracist teacher is for a different system and set of practices that is opposed to the racist ones we have now, the systems that many only know.

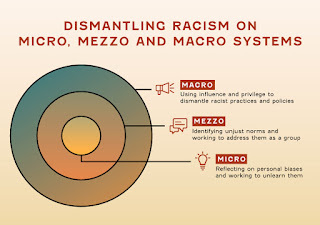

Orienting yourself as an antiracist teacher is orienting yourself at all levels, macro, mezzo, and micro (see image, note 129). It's orienting yourself for an educational system that is not the current unfair and racist ones, as well as for pedagogies and materials that acknowledge such institutional and structural racism. It doesn’t let the racist system or our own language habits off the hook at any level, which includes interpersonal interactions and our own ideas and ways of seeing or understanding our students and their languaging. This orientation names as racist the status quo of school institutions and their goals for students, the language structures and disciplinary knowledge we all inherit to become teachers, and even many of our personal perspectives cultivated from our White supremacist society. It also keeps present and foremost in our minds what we are trying not to engage in, racism. Remember, not mentioning race usually allows racism to maintain itself. You can be inclusive about all kinds of stuff, but that don’t make you antiracist.I suppose we could say that the teacherly orientation I’m calling for in this blogbook is not just an antiracist one, but also an explicitly political and racialized one, one that is conscious of the importance of the politics of race in the teaching we do. So it’s also a racialized and political orientation. The problem with this language is that sometimes it can appear as if we don’t have racist problems in our systems and schools, in our classrooms and assessment practices, in the very disciplines that make us as teachers and educators. That is, if we name our orientation to teaching as one that is just political, we might end up ignoring what kind of politics we are focusing on. There are many that are important to address: gender, sexual orientation, spiritualities, class, geography, etc. So if we’re interested in racist problems, then our orientations should be against those particular things and we must name those things, even as they are always implicated to other social dimensions of our lives.

This means we must embrace conflict and understand it differently than merely “against” something else. That is limiting, and quite frankly, Whitely (note 130). Using more facially positive terms, or ones that seem to provoke less ire by others, can also lead to teachers talking past each other. That is, people who seem to be discussing the same topic, even agreeing generally about their purposes and goals, but really, they aren’t engaging with each other. They are talking about different things, and it always leads to reinforcing White supremacy. That’s the game.

One teacher is talking about breaking racist systems by NOT talking about racism, by being positive only, so they talk about inclusion and valuing other ways with language. They talk about “closing achievement gaps.” They talk about helping “underprepared” students or “disadvantaged” ones, making special classes -- all code words for BIPOC and deficit. This kind of language participates in the old Southern strategy of racist discourse (note 131). Talk about race by not talking about it. From this orientation, it would appear the system is okay. It just needs to add some inclusion, a text from a Latine or Black author, a helpful course or tutor. “How would you say that at home with ya momma?” “Now, let’s translate it for school.” “Take this course, it will help you succeed and achieve.”

Meanwhile an antiracist teacher is talking about dismantling curricula because it promotes only a White European set of languages and values, and makes it harder for most of the BIPOC and poor students in their classroom to achieve success. Success is defined in elite White racial terms, languages, and habits of learning. They push against the grading of their students. They openly criticize department standards for writing. They want to decolonize the reading lists. This teacher is saying, “we are linguistically and intellectually colonizing our students into an elite White system only.” They tell their students: “The system playin’ ya.” “Ya gettin’ gamed.” “It’s makin’ ya think you ain’t good enough or too stupid to achieve,” while it hides its elite, White standards behind the smoke of raceless, universalizing language that just ain’t true.

The first teacher is ignoring the system by not acknowledging the fundamental White supremacy of it, while the second teacher is addressing it as already politically raced and pushing to dismantle it. They are not talking about the same kinds of goals. But when we place both teachers into that same system, say a school, classroom, or a faculty meeting, the first seems more positive, more palatable, more agreeable, more helpful, because they are doing diversity and inclusion work as the system has prescribed it. The second teacher just seems like a troublemaker.

But in the end, when history rolls on, the antiracist troublemaker-teacher will be the one who makes things more equitable for all if given the chance and joined by co-conspirators. If the system is racist, you gotta make trouble for it. Don’t let it co-opt you or your practices. Don’t let it alienate you from your work, your life, or students.

This talking past each other is also a White supremacist strategy that avoids the actual conflict, as if conflict is abnormal or bad. Conflict, tension, difference, disagreement are typical and normal in human societies. Conflict and the confronting of difference is how people and systems change, how we all learn new things and grow. If you want to be a faster runner next year, then you are trying to be a different runner than you are today. Your practice, diet, and other habitual behaviors are designed to change you, to make you someone different, even if incrementally.In this scenario, you embrace the conflict between being a different runner today than the one you strive to be tomorrow. The same goes for racist systems and our own views of things. You want to be antiracist but you don’t know how? The system hasn’t seemed difficult or unfair to you? It’s hard to understand all the ways you are privileged? Then you need to change your orientation, to be different, so that you can see, feel, and understand things differently -- from a different position in the system. This repositioning, or reorienting yourself, is a way to create inner conflict in order to make you better. So why demonize conflict? Why be afraid to disagree? Why be afraid to be against a racist system? Conflict, if done meaningfully and compassionately, means change is coming.

Many of you may be thinking that this is all well and good, but you need something practical. First, let me warn you about that impulse. It participates in habits of White language that often turn into White language supremacy in schools and other places (I’ll talk about this later in this blogbook). It also infantilizes you as a teacher. Don’t settle for other people’s answers. Settle for your own, but learn about why and how others do what they do. Anything practical or “how to” that I might offer you here should be read with a grain of salt. Like everyone else’s practices, mine come out of me and my conditions (or lack thereof).

Having said that, I can say this: What it means to be an antiracist teacher is to have an antiracist orientation to your work, your planning, your school, your students, your own body and subject position in the classroom. The elements I offer below are meant to help you find an orientation that leads you to your practices. If you just take my example practices alone, then you risk not being antiracist because you don’t have an antiracist orientation. And without it, you are vulnerable to the White supremacist system, one that will co-opt you and your practices. Again, the racism in our systems is overdetermined, coming at us from many angles and places.

In my own and other literacy teachers’ antiracist orientations, I have found twelve common elements, some are impulses and urges, some are goals and purposes, while still others are flexible practices or behaviors that may look different in different places. All are important, so I find it difficult to cherry pick from them, then call myself an antiracist teacher. But many of these things are hard to do, and doing them all at once is a pretty monumental task. We must have compassion for ourselves and an understanding of our limitations, while pushing ourselves toward discomfort.

I’ve grouped them into three categories for convenience’s sake. These categories may help you think about the areas of your teaching life that can be reoriented. You may even find other elements to add to this list of twelve. I’ll discuss each in more detail in the next entry to this blogbook. Below I just want to offer the list as a generative set of incomplete ideas.

A teacher who embodies an antiracist orientation . . .

Compassionate Politics and People

- pays attention to the intersectional subjectivities in the classroom

- calls attention to the racial politics of language and its judgement

- deeply attends to everyone in the classroom

- forms agreements with students about compassion

- uses collaborative processes and negotiation with students to build everything in and around the classroom and to determine students’ learning in equitable and fair way

- crafts antiracist purposes and goals

- measures success by the antiracist outcomes of a class, lesson, or activity

- is continually interested in conflict and difference of opinion or perspectives

Curricula and Materials

- integrally incorporates materials, literatures, and writings from BIPOC scholars and writers throughout their curriculum

- resists hierarchical logics as a way to organize the classroom, materials, ideas, assessments, students, and their language performances

- incorporates racial theories and histories into all their lessons and activities

- focuses on labor in order to define the effectiveness and efficacy of assignments and lessons

---

This blogbook is offered for free in order to engage language and literacy teachers of all levels in antiracist work and dialogue. The hope is that it will help raise enough money to do more substantial and ongoing antiracist work by funding the Asao and Kelly Inoue Antiracist Teaching Endowment, housed at Oregon State University. Read more about the endowment on my endowment page. Please consider donating as much as you can to the endowment. Thank you for your help and engagement.

Comments

Post a Comment