Blogbook -- Brave Classrooms Ain't Safe Classrooms

Entry 24

As items 3 and 4 in my list of habits that make antiracist orientations of teachers suggest (from post 22), I find it important to form agreements with students about what it means to be compassionate and brave in classrooms. Bravery in literacy and language classrooms is necessary if we want to fully and compassionately address White language supremacy. As I’ve suggested up to this point, you cannot do antiracist work without talking about, dealing carefully and continuously with, race, racism, and White supremacy in our languaging, judging, and literatures. Without being brave in a particular way, it is almost impossible to do any of this work.

And bravery is not safety in the conventional sense if safety means we don't risk changing.

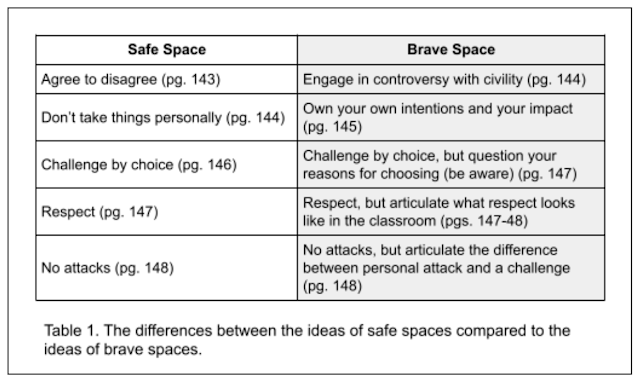

When I say “brave,” I’m drawing on Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens’ chapter, “From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces: A New Way to Frame Dialogue Around Diversity and Social Justice” (note 138). In their chapter, they discuss ways to have brave conversations about race and racism in school settings. They describe such discussions in opposition to the traditional language of “safe spaces,” opting instead for “brave spaces.” They take a number of common rules that tend to regulate safe spaces in classrooms and offer alternative language that can transform a safe space to a brave space for hard but meaningful conversations about difference, social justice, race, racism, and of course, White language supremacy (although they don’t name this last one).

I’ve made a table below from their chapter that may help show the differences. It offers some ways to discuss with students how to cultivate the classroom as a brave space in order to investigate White language supremacy and racist discourse. I’ve included page numbers from their chapter for reference.

Notice the shifts in how engagements and discussions happen in brave classrooms. Brave classrooms accept respectful conflict and challenge as important to their goals, and this is a feature of antiracist orientations discussed earlier. A brave space doesn’t avoid conflict or questioning of others’ ideas in order for everyone to feel artificially safe. It embraces a respectful and civil kind of conflict as a compassionate and caring response in a community or classroom.

What respect and civility look and sound like are explicit agreements that are usually discussed up front. These agreements of what civility and respect mean allow students and teacher in the brave classroom to care enough to be honest with each other and reveal differences of opinion. Brave classrooms look for controversy and differences of perspective in order to mutually develop complex understandings of racial questions and issues, as well as of language and literature.

Brave Work

Write for 10 minutes.

Consider the five statements in Table 1 that describe brave spaces or classrooms. Now think of the last difficult conversation your students and you had.

How did your classroom NOT accomplish or encourage each of the five statements that define a brave space? In what ways have you and your students not been able to be brave? Why have you not be able to accomplish this?

Brave classrooms also urge everyone, including the teacher, to be responsible for both our intentions and the impact on others (long and short term) of what we do and say (check out the short video below by Dr. CI on impact vs. intention). Falling back on explanations for our words and actions that amount to “I didn’t mean to cause you harm,” or “my intention wasn’t to offend you,” is not enough in brave classrooms. That isn’t being brave. It’s being defensive and insensitive to others’ hurt. It’s protecting your own feelings and ego, not helping others with the wounds you helped cause, even if unintentionally. Because conflict and differences are purposefully revealed, there will be offenses and hurt feelings. They cannot be hidden or ignored if we want to overcome them in the future, or find ways through them together.

If I’ve hurt or offended you, it doesn’t help you or me by you being silent about it, nor by me relying on only my intentions for doing no harm. Both strategies disregard the racist outcomes that exist in the classroom space. Furthermore when you challenge me, I have to be brave enough to accept your challenge as a compassionate and caring response to me, one that helps both of us, and our colleagues around us. We are not simply trying to better ourselves as individuals. We are trying to help our community as an individual with others. We are trying to take responsibility for the health and equity of the entire classroom, of all of us together.

This means that I have to be able to judge my intentions separately from their outcomes or impact on others. Both are important, but the racist impact of our words or actions is primary. And of course, your challenge to me cannot be a knee-jerk, tit-for-tat response. It must be one that seeks to help and reveal for everyone’s sake. It must be given respectfully and compassionately. Ultimately, this kind of classroom asks everyone to measure their contributions not simply by their intentions, but mostly by how their languaging affects others around them, how they can help others, how they suffer with others, and how we all forge solutions forward.

Doing this brave work helps everyone understand better opposing ideas, people, and perspectives. It makes explicit that when someone chooses not to engage or challenge another in a discussion, say about White language supremacy, they are doing so from a position that affords them that ability. They are also not participating in the brave classroom. They are not taking on a share of the responsibility of an antiracist classroom. Brave classrooms deeply and continually examine White language supremacy and racism in our language practices, texts, and standards. They don’t avoid such discussions or minimize them. These are our responsibilities.

Those who avoid such brave discussions are choosing, out of a privilege to do so, a stance that is not defined in the classroom as brave, instead they are doing something else. Usually they are protecting someone’s feelings by not helping them see or hear the impact of their actions or words. But in protecting the offender, they doubly hurt those who have been offended or hurt.

When everyone acts bravely, they question their motives and their privileges to not engage. And sometimes, depending on the circumstance and people involved, just any time may not be the right time to engage deeply and bravely in particular race discussions. We should be compassionate to ourselves as well. But we should also notice and make an account of how often we chose not to engage, not to accept the challenges presented to us.

Derald Wing Sue, a professor of clinical psychology at Columbia University, also offers a number of good ways to set up guidelines and practices for difficult race discussions in classrooms and other spaces. They agree with the ideas of Arao and Clemens’ notions of a brave space. I highly suggest his book, Race Talk and The Conspiracy of Silence. In it, Sue offers five “guidelines for taking responsibility for Change” that individuals can use:- “Learn about people of color from sources within the group”

- “Learn from healthy and strong people of color”

- “Learn from experiential reality”

- “Learn from constant vigilance of your biases”

- “Learn from being committed to personal action against racism”

There is a lot to say about each of these imperatives. Most important for my discussion is to see or hear in them how they help craft an antiracist orientation in everyone, teachers and students. These are lifelong habits, not a checklist to knock out over a summer of reading. Antiracist orientations are not just for teachers either. Students can and should cultivate theirs as well. In fact, practicing these five imperatives exercises several of the elements in an antiracist orientation (items 1-3, 8-9, and 11).

Sue also offers two other important lists of strategies in race conversations, which can aid teachers and students. They amount to a list of do’s and don’ts for brave classrooms. I list them in the table below for ease (note 139).

Again, I hope you can hear many of the items above in the right-side of the table in my description of antiracist orientations for teachers. Sue’s list is framed for both students and teachers, I think. They may be a good starting point for a classroom’s goals or ground rules. A few things I’ve not highlighted up to this point in the positive actions listed above on the right side of the table are worth noting.

The first is items 4 and 5, ones about understanding and acknowledging the importance of our feelings in race conversations. We don’t always get to control our feelings about things, especially things that can be interpreted personally, like when I say, “some students in this classroom have been privileged in school by the lucky chance of being born into a White family who speaks a middle-class White English language. Your success is not all of your own making. Your position in White language supremacy matters to your success.” That can sound like I’m saying that those students don’t deserve the successes they’ve gotten. But that’s not what I’m saying at all.

It’s important for a brave classroom to dwell on why some may hear something else and feel hurt or guilty or upset about this systemic fact, and what it means to those not born in such circumstances. In White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard For White People To Talk About Race, Robin DiAngelo discusses in detail why many White people have such responses or feelings about statements like mine above.Additionally, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s book, Racism Without Racists offers rhetorical frames and language that many White people use to defend their racism or explain it away, minimize it, which also can help us all understand our responses and misunderstandings about systemic racism (note 140).

The second emphasis in Sue’s list above that I want to call attention to is the process- and procedures-based actions of items 6, 7, 8, and 10. Following these actions can help create the right kind of brave conditions for productive and meaningful discussions. It can also provide the teacher with ways to respond, especially in difficult situations, perhaps when a serious disagreement has occurred.I don’t think it is a good idea for a teacher to take sides when students disagree or form opposing arguments about difficult topics, such as White language supremacy. But I do think it is important to have meaningful ways to be honest about our (teachers’ and students’) subject positions and the politics that travel with those subject positions. This means that we need ways to engage with our students, acknowledge all of their ideas and feelings, even when we do not agree with them. We cannot force students to believe or understand things in our ways or in our timelines, but we can model behaviors and languaging that demonstrate that everyone's personal ideas come from certain places in our lives, all our feelings are important to us, and no one gets to have a monopoly on objective truth or how to respond to things.

Brave Work

Write for 15 minutes.

Consider actions 6, 7, 8, and 10 listed on the right side of Table 2. Use these as a set of priorities to sketch out a discussion on a hard topic about language and race, for instance, “why don’t we allow Black English to be used by lawyers in courtrooms and in their writing of legal briefs? How is this one example of White language supremacy?”

How would you use all four of the actions listed as a way to design this discussion with your students? Try to also list out ways you might respond in difficult moments of the discussion, say, when there is disagreement. What things might you say or do to help the conversation meet its goals?

Thus, the unmasking of difference (#7) in the above list can look like a teacher simply identifying where and how students disagree or are positioned differently, without making any evaluative judgements on the positions or ideas or words in contention. There is no need to take sides. That is not the point of race discussions. The point is to hear others as completely as we can, to suffer with each other through a topic or discussion, and use these practices to learn, to grow, to change in ways that make for more sustainable and equitable futures. Practicing this imperative might sound like a teacher pausing a discussion to say something like:

Let’s pause a moment and listen to what’s been said. What I hear Keith saying is that language is objective rules for communicating. Language has nothing to do with race or White people, or any group. It’s just how people communicate, so we all have equal access to it. Vee is saying that language is made from people. It has to be formed from what people are made of or have available to them, like gender, race, economics, and class -- their experiences. It can’t be neutral because people have biases. Now, class, what do you think is required to accept each position? Let's start with language as objective rules, then we’ll go to language as part of a group’s biases. How can each be reasonable and true?”

Controlling the process (#6) can work with planning purposeful investigations with students (#10), and this can help limit and control what happens and what can happen, what ground the class is looking to cover, and how the class plans on traversing that ground. It really amounts to a special kind of preparation. It’s wonderful when the unexpected happens in our classrooms, when magic bursts out and students are energized in ways you didn’t plan for. But this is not a good practice to lean on in order to achieve good learning.

Using mostly the unexpected magic in classrooms as the main way we hope students achieve learning goals is essentially leaving learning up to chance. It’s not viable pedagogy. And it tends to reinforce hegemonic, White supremacist positions and ideas. Because we are in White supremacist systems, we tend to gravitate to White supremacist behaviors and ideas. This is what such systems produce because they are made this way. When we leave things to “chance,” when we only “hope” for the best, it is another way of leaving things up to the system to determine.

But item 6 above really is more than determining how a discussion will move or flow, who will go first and for how long. It’s also about what happens when we talk, and what gets focused on in race discussions. Too often, race discussions get derailed by strong emotions, or tangential topics that sidetrack everyone. Both keep the group from having the discussion that was originally planned.

For instance, take my example of a teacher unmasking the difference in points of view above. In that conversation, a classroom is talking about the ways elite White people have controlled standards of appropriate English in schools and how they have benefited from that control. It’s not hard to imagine that someone will get upset and say something like: “that’s stereotyping. My family is poor and White, but we don’t get to control language. Don’t lump me in with others. All groups are diverse and shouldn’t be stereotyped. This is more about money and class. I ain’t got no power.” It’s important to recognize this student’s valid feelings and experience. It’s also important to continue the discussion about the topic at hand without derailing it.

The teacher can notice and pull out the pertinent parts of the student’s response, while also acknowledging that the student feels like they are being unfairly judged or blamed. The teacher might respond like this:

I hear that you may be feeling unfairly judged, Kay. Thank you for being honest and brave. I can tell you are taking our discussion seriously. This is helpful. Let’s all keep in mind that our statements about how language is judged in schools are not about individual people, or blaming them or making people feel bad. They are about language itself and how systems around us are made, like our course’s standards and learning outcomes. Let’s also remember that all of our feelings about these ideas are important to us. We all have the right to our feelings about these ideas. Let’s try to understand both our feelings and the ideas and facts we have in front of us.

What I also hear in Kay’s response is that many White people don’t have the same privileges or language that tends to be rewarded in school. There is unevenness, or exceptions to the larger patterns in our society. Furthermore, I hear Kay saying that language comes from a middle to upper class White group of people and perhaps those who have money and power in the world. Is this accurate, Kay? If so, what else do we need to know about how language is judged in schools to figure out what we can do with this new information? It sounds like we are talking about exceptions and rules. What do we understand from the facts in front of us? How do we use Kay’s concerns in a way that helps us be more critical about the politics of language that we’re discussing?

This pausing to notice what is being said and how people are feeling can keep the discussion from being derailed or hijacked by the emotional feelings of someone in the room. But those emotional responses are wrapped up in other important information offered by Kay. The student’s feelings are important to acknowledge. At the same time, there should be a balance between that and overly shielding the student from facts and ideas that cause the emotions.

It’s perfectly legitimate to have and express an emotional response about such topics. It means the student is taking the discussion seriously, engaging seriously. The teacher’s response shouldn’t ignore those feelings, but separate them from the other information that the class can work with. Derald Sue calls the emotions and ideas underneath, or interlaced with the other ideas, the “hidden transcript,” or the stuff under our words that require a teacher to compassionately guide folks through in order for the discussion to move forward in the direction everyone agreed on up front.

Brave Work

Write for 20 minutes.

Look back at the last classroom activity you designed and conducted that dealt with a difficult race topic or text. This might be a discussion of a text like, To Kill a Mockingbird, or a discussion of BLM (Black Lives Matter) demonstrations.

How exactly did you set up or prepare your students for the activity? Did you provide any written forewarnings? Look at exactly what you provided, the exact words (hopefully you have them), then notice the way you framed the activity, its goals, and students’ orientations to the discussion. Did you ask them to be brave? Did you acknowledge any feelings as important? What did you focus their attention on in order to prepare for the discussion? How was your preparation different from what Sue suggests?

Item 10 is equally important to 6. It prepares students for the potentially difficult discussions ahead. Sue offers an example of a forewarning for workshop participants that is worth providing in full. It prepares participants for discussions. It also frames the workshop in a way that helps orient people before they even get there.

This is a workshop (or class) on race and racism awareness. We are going to have some difficult, emotional, and uncomfortable moments in this group, but I hope you will have the courage to be honest with one another. When we talk about racism it touches hot buttons in all of us, including me. Being honest and authentic takes guts. But if we do it and stick it out, we can learn much from each other. Are you willing to take a risk so that we can have that experience together? (note 141)

Such preparatory statements can be offered a day or two before hard race discussions occur in class, then reinforced before the actual activity.

Often in my own writing classes, I ask students to do a little reflective writing about what they think may be difficult for them to discuss and why. What are their hot buttons? We then talk about what they wrote. I don’t try to convince them not to be worried about things they think they will have difficulty with. I only try to help them see that we all have such hot buttons and anxieties. It’s a way to acknowledge equally all of our feelings, show them as important, but also build pathways through them in order for the class to accomplish its goals. I may close such discussions with a short writing that asks them to consider what they can do to prepare themselves for the upcoming discussion. Can it be okay to have some anxiety or strong feelings about the topic, knowing that we all are trying very hard to be compassionate to each other? Is it bad to feel strongly about a subject in school, one that also can be engaged with intellectually?

The goal of all exchanges around White language supremacy is not to determine a winner or correct position, but to see how other positions and perspectives can be reasonable, how they can be true from another vantage point, from another history, and from another body that is treated differently in the world, and then find ways forward together. Our goals in such classrooms are to grow together, move forward together, cultivate benefits for others, not just for ourselves. Equally a part of this goal is to acknowledge the paradox discussions create. We all have the right to our ideas and judgements, even as some may hurt others or cause outcomes in the world that are White supremacist. What do we do when some people’s views of language create unfairness and inequality? How do we move through this paradox? How do we do equity in our languaging?

We don’t always have to give up our initial positions or ideas about language and race, but we should seriously and bravely set our ideas of them next to others’ for a time, consider from historical and other evidence what each view of language and race creates in the world and be willing to change unconditionally. That is, we too often set unrealistic criteria for our own growth and change on difficult topics, like racism.

For example, we may tacitly think that we’ll only change if that change doesn’t interfere with other ideas we have, like our own senses of how we’ve succeeded in school, or our notions of our own merit and ethical positions. We may unknowingly set criteria that dictate that we will only change if that change doesn’t make us feel uncomfortable, or guilty, or sad, or upset. These are not conditions for personal change and growth. They are conditions for not changing and not growing.

Change is often unsettling. Learning and growth, the really good, strong, amazing kind, can often be paradigm-shifting, or ecstatic, or heart-wrenching, or soul-searching, or like the slow moving of sand on a beach, decade after decade. But if we are bravely growing, we have to allow ourselves to be open enough, generous enough, compassionate enough to let ideas and other people’s languaging really change us. And I think, we have to consider letting our changes happen not for us, but for others around us. We learn, and grow, and language in our classrooms for those around us because those around us are also trying to learn, and grow, and language for us. And that is a brave classroom, but it ain’t a safe one.

This blog is offered for free in order to engage language and literacy teachers of all levels in antiracist work and dialogue. The hope is that it will help raise enough money to do more substantial and ongoing antiracist work by funding the Asao and Kelly Inoue Antiracist Teaching Endowment, housed at Oregon State University. Read more about the endowment on my endowment page. Please consider donating to the endowment. Thank you for your help and engagement.

Comments

Post a Comment