Blogbook -- The Politics of Whiteness in the Logics of Outcomes

Entry 40

In my last post (post 39), I discussed the ways white male authors and their historically cultivated habits of language deeply inform the CCSS and its appendix essay, which explains the focus on “argument” over “persuasion” when teaching language and writing to high school students in the U.S. But I was just getting started in explaining the problems with the appendix essay and the focus on argument. There’s more. I’ll continue in this post. The reason I go into such detail about the appendix’s discussion is that it is indicative of most logics in all course or programmatic outcomes, in both secondary and postsecondary contexts, and it’s good to know what we must orient ourselves against and why if we wish to be antiracist.

The appendix’s discussion of “writing” explains three kinds of writing students should learn: “argument,” “informational/explanatory writing,” and “narrative.” However, half or more of this larger section in the appendix on writing focuses on writing as argument. In the subsection called, “The Special Place of Argument in the Standards,” the authors explain: “While all three text types [of writing previously explained] are important, the Standards put particular emphasis on students’ ability to write sound arguments on substantive topics and issues, as this ability is critical to college and career readiness” (note 276).The same subsection ends with a conclusion from another white male professor of English, one who is conservative in his arguments, and one who argues against using the politics of English in classrooms. Richard Fulkerson believes that teaching writing can be a neutral practice of learning to use words and rhetorical moves alone (note 277). The conclusion in the appendix states:

The value of effective argument extends well beyond the classroom or workplace, however. As Richard Fulkerson (1996) puts it in Teaching the Argument in Writing, the proper context for thinking about argument is one “in which the goal is not victory but a good decision, one in which all arguers are at risk of needing to alter their views, one in which a participant takes seriously and fairly the views different from his or her own” (pp. 16–17). Such capacities are broadly important for the literate, educated person living in the diverse, information-rich environment of the twenty-first century.

There is much wisdom in entering language exchanges where risk-taking is central and altering one’s initial views is understood to be important, even necessary. There is much value, as I’ve mentioned already, in arguments that are not victory-oriented but concerned with making “good decisions” and listening to “views different from” our own, or as Williams and McEnerney say, “getting to the bottom of things cooperatively.” I too see these things as “broadly important” “capacities.”

But we don’t work or do language broadly or in the abstract, and focusing primarily on words alone, on logos, on argument as the CCSS understand it, may not accomplish good decisions from different points of view most of the time in or outside of the academy. Remember, we are creatures of location, of place. We language in particular situations, with particular people, from particular political locations and histories, and for particular purposes. Good teaching and learning of writing will pay close attention to all these particulars and name them appropriately. Good language teaching pays attention, for example, to words that project the ideal student-citizen in the above passage, one who is “literate” and “educated,” which too often means middle class and white, and perhaps even male, but not trans. A critical reader (and writer) might notice that such phrases as “literate, educated person” easily participates in elitist ideas of college-educated people versus others, say, working class people, ones not college “educated” or college “literate,” nevertheless educated and literate in other ways and must make important decisions all the time.

In fact, Graff – remember, the CCSS appendix authors quote him first – taught us a version of this lesson in his article, “Hidden Intellectualism” (note 278). In the article, he makes the argument that adolescents outside of school culture learn to argue in ways that agree with academic argument culture, even if those habits of language may initially look or sound different. Ultimately, Graff argues that such outside cultures of argument actually help schools and classrooms teach argument, or can help them if they recognize argument as universal.

However, Graff does not investigate his own white working class background as such, which he draws on heavily in the article, ignoring the very real intersectional differences in languaging cultures that accumulate when we take into account race, neurodivergency, gender, geography, and multilingualism together. He also doesn’t account for the racial, classed, and gendered politics that affect the way all language is judged in any situation. You cannot have a strong argument or a compelling one if you don’t have people who agree that it is so and who act on that agreement. They also have to have some criteria by which to consider some instance of language as compelling or strong. Where do those ideas and criteria come from? We know the answer: white, middle class, masculine habits of language. And these hegemonic and determined judgements are made in conditions that are formed by hegemonic and determined political arrangements. In effect, as I read Graff and the CCSS appendix, this racially blind logic simply reasserts elite white masculine habits of language as nearly universal ones about some kind of universal argument culture.

And of course, racism can be produced in classrooms that use such assumptions about a universal argument culture, even as no teacher or administrator can be blamed for intending to be racist. The copious research on implicit racial and other biases testify to this problem in all of us (note 279). Our implicit racial biases are structured into our society, and so are structured into each of us. Again, Graff’s article is an example of this. He is far from attempting to enact racist pedagogy or ideas. In fact, most readers I think would say he’s attempting antiracist pedagogy, although I don’t think he ever calls his work that. Yet, his own implicit biases, ones that don’t allow him to recognize the importance of political and other differences that are organized by race in classrooms, create his racially blind pedagogy. These biases furthermore are structured in all of us from our disciplines and even society. The fact that such a disciplinary document as the CCSS uses Graff and Fulkerson without a comment about either man’s racial politics is one way to see how deeply this problem runs in disciplines.

These structures I’m talking about are outside of people and their biases, yet they also help create our internal biases, most of which do not seem to be about race, gender, ability, or socioeconomic factors. Is the janitor at the school where the CCSS is used also included in being a “literate, educated person living in the diverse, information-rich environment of the twenty-first century”? How are their habits of language honored and valued in the CCSS? And who racially and statistically speaking is that janitor in that school anyway?

These are structural and historical problems, many of which are not controlled by a teacher. And yet, our classrooms and teaching, our students’ learning, are situated in such systems that overdetermine the white language supremacy of the CCSS. Is it surprising that all the experts that this appendix uses to explain the CCSS are white males? No. This fact is determined in a number of ways by the system, by history, by the discipline of Rhetoric and Composition, just like the overdetermined nature of the whiteness of the Pac-12 college writing program directors that I discussed in the last post.

Here’s another test of white language supremacy in your classroom: Who were your English teachers and professors that trained you? Who teaches English in your school? Who are the principals in and the superintendent of your school district? What are their language habits and dispositions? If the authors of the appendix do not pay attention to such important racial, gendered, and linguistic aspects of the arguments they marshall and the bodies from which those arguments come, the structural white supremacy will be maintained without anyone noticing. And we’ll all keep wondering why things don’t change.

But of course, the authors of the CCSS did not pay attention to the subject positions and politics that go with those they marshal to support their cause. They look only at words, and ironically miss lots of important parts, places, politics, and people in this discussion. They miss the politics of language and its judgement. They miss the whiteness of what they ask for, and likely wonder, why are all the Black students so far behind? When you only look at the words, it’s hard to see all the BIPOC voices and women’s voices, and trans voices, and neurodivergent voices, and working poor voices who are not represented or heard or even considered. It's just the same elite white dudes telling everyone how good their white languaging is, and that it’s not political or racial, just English, plain and neutral. Everyone can or should learn it – that’s what’s fair and right, they say.

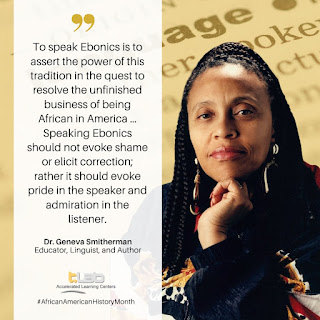

Black Linguist Who’s Been Sayin’ for Some Time

If these authors had tried to consider the racial politics of language and logos in their own argument for the CCSS, they might have come to a different conclusion. They might have found the Black woman scholar who has been doing important language work for decades, at least since the mid-1970s, Geneva Smitherman (note 280). They might have paid attention to Smitherman’s arguments for Black English and tempered Fulkerson’s words with hers. She speaks of politics and racialized bodies in literacy classrooms and the then (mid- to late 1970s) critiques of the American educational system:As a result of these recent critiques on American education, it is finally being recognized that the school plays a tremendous role in shaping the values and attitudes of tomorrow's adults. (Like, everybody and they Mama pass through school even if they don't stay too long, right?) Schools have potentially strong influence upon their captive audiences. Traditionally, they have used that influencing energy to give sustenance to an unjust, dehumanizing system. Students of the 60s -- peered behind the mask of “liberty and justice for all” and gazed on the awesome monster of privilege and advancement for a few. Many of these same students helped to strip away that mask for all the world to see. And some of them, using a protest borrowed from the black liberation struggle, even tried to transform the hideous creature into something of beauty and value.

… For if it is true that the schools do not properly serve white middle-class students of the contemporary world, they do a great disservice to black students. For the American school, with all its defects (as the great Dr. Carter Woodson would say), continues to be basically oriented toward and supportive of a lifestyle that coincides with that of the dominant culture. The message conveyed by this white middle-class orientation is that the black child has nothing of value and thus he or she must be uplifted and properly socialized by the school. (note 281)

Her focus here is on institutions and history, structures that we work in and that make us all. It is not hyperindividualistic in its orientation. Smitherman ain’t talkin’ just about individual students succeeding by their own merit and pluck in so-called meritocratic systems of grade-competition. She ain’t asking to teach no conflicts. Who needs teaching a fight you can’t win, or rather one you gotta fight on someone else’s turf with their rules. She’s speaking in pluralities, in terms of communities, schools, systems, and in the ways those schools serve people in unequal ways by design. She implies slyly: There are other designs.

She’s also saying that the current schools form a “dehumanizing system.” She points our attention to student movements that looked to change such systems, movements that came out of Black liberation struggles -- Black people leading the way. She points to the uneven ways that these school systems, language systems, do not actually work well for anyone, white or Black or Brown, but work worse for Black students. And she pins this dehumanizing system to a “white middle-class orientation.” She’s talking about HOWL and white supremacy culture (see post 28). There’s the root of the problem in the literacy and language classroom. Others more recently agree. I’m thinking of books by Battina Love, April Baker-Bell, Carla Espana and Luz Yadira Herrera, and Carlin Borsheim-Black and Sophia Tatiana Sarigianides (note 282).

Most of Smitherman’s book, most of what comes before the late passage above, shows in great detail the ways Black English is elegant, communicative, logical, and effective. She demonstrates many ways in which there is no deficit, only differences, ones contingent on the racialized histories, places, people, and politics involved. Smitherman keeps the racialized embodiments of students and teachers in her discussion and in the classroom. In short, Smitherman does not come to the same conclusions about language that Fulkerson or the authors of the CCSS do. There are politics, structures, and racialized students and teachers in the classroom for Smitherman. We ain’t never teachin’ just words. We teach in, through, and hopefully against white supremacist structures too – or we should be.

And to do as Fulkerson aruges, to take “seriously and fairly” other views different from one’s own is not a simple task. It is political in nature, requiring us to recognize those politics and teach languaging with them. But there are more fundamental problems with these anchor standards and their justification by Fulkerson. What if, for instance, we do not agree about what a “good decision” looks or feels like, say on how to teach English in antiracist ways, as Fulkerson and I likely do not? How shall we proceed cooperatively? How will we take our risks together? Who will be more at risk, a white man living in Texas (Fulkerson) or a man of color living in Arizona (me)?

Won’t I, given who I am and how I have been situated in the world, have to take bigger risks as a teacher of color than Fulkerson? And what about a woman of color teacher? Doesn’t this teacher have more at stake still, more to gain, more to risk? Or just different things at stake and to risk? Doesn’t the white male teacher have more to lose? Would it feel to the white colleague that the other’s gain is his loss? And given that they likely have spent a lifetime already, as short or long as it may be, making compromises and waiting, do you think the teacher of color may be less inclined to compromise yet again on antiracist ideas with yet another white person who appeals only to reasonableness and logic?

“Being reasonable” and focusing just on “logic” has tended to be a delay tactic by white people with power who have less urgency for change. I mean, things are fine for most white teachers and students now. Learning English in school doesn’t feel like someone taking part of your heritage away, part of you away, does it? And these white colleagues may say, “we should get this right. Let’s be reasonable and accurate. Let’s take our time on it.” This is a great way to do nothing while appearing to do something by only talking about change. The differential in power, in the positions we each hold on the landscape of argument and opportunity that is at stake, are not the same for BIPOC and white teachers or students.

Politics, that is, relations of power, relations to the habits of white language in the CCSS, relations to the racialized and gendered bodies that have made such habits dominant in disciplines and schools, all dictate that there are different consequences for those in the debate. This means teaching ethical and sustainable argument is also about the people and their bodies and histories in the room. Shouldn’t this fact of arguing from different positions, which assumes location and embodiment, be an important part of the teaching of writing. Shouldn’t it too be in the CCSS standards? Wouldn’t doing so make such an outcomes statement more antiracist?

Bodies in An Argument over Teaching Writing

Fulkerson, in his other work that surely informs his textbook cited above, asks us to ignore all these things. In fact, the CCSS standard might be saying that we should focus not on differences among arguers but merely differences among arguments, words, claims, and evidence presented in writing. If you did the latter, you’d miss most of the guts and significance of any argument, not to mention the ethical dimensions of the positions in the debate, and perhaps Smitherman’s important work. In fact, my discussion of the CCSS Appendix A, over the last few posts, has been one that does not simply look at the words quoted or used. And there is a lot to say, to think about, to consider that circulates around these words, but are not purely logos.

Here’s what I mean. Fulkerson is a conservative white, male professor from East Texas State University (now, Texas A&M University -- Commerce). You could miss all the above meaning in his words quoted in the appendix, if you didn’t know this. His words seem reasonable, and that is because they are that. And this can be a problem if part of what we teach when we teach language isn’t also working through how we have come to be in classrooms and societal conditions that mostly allow an argument like Fulkerson’s to be “reasonable,” to be understood as reasonable. How and who have defined and deployed the idea of being “reasonable”? Who has benefited from such deployments of “reasonable” talk? Put more bluntly, what are the racial and gendered politics of what we have come to understand as “reasonable” in language?

Fulkerson’s other arguments about teaching writing in college focus on taking politics out of the writing classroom. His idea is that the classroom should be just about words because there are no politics to words. It’s how words are used that make for politics. This ignores the conditions in which we all live and circulate words. It also ignores the different ways each person comes into a space to argue or offer words. Fulkerson says that teaching should avoid the political, not indoctrinate students, not focus on critical cultural approaches to literacy because those approaches primarily indoctrinate and not teach writing.

In defending Maxine Hairston, who made a similar argument against critical cultural studies (CCS) approaches to teaching college writing, Fulkerson explains that it is an “obvious absurdity” to think that all pedagogies are “equally indoctrinating.” The position Fulkerson speaks against is that we all have politics, so we must lean into it a bit, acknowledge our politics in our classrooms, not avoid them or pretend they don’t exist. But as I understand the situation, all pedagogies are political and all languaging is political because people are the essence of the political, and these conditions do not need to be a bad thing. Acknowledging our bodies’ and languages’ politicalness – that is, acknowledging the ways in which each body’s languaging is judged differently for a variety of reasons – in our classrooms is not indoctrination. It is helping students understand the terrain on which we operate.

Fulkerson responds by arguing that rhetorical pedagogies, ones that could be read in this anchor standard and the CCSS, are not as indoctrinating as others, and so preferable. They are about mostly neutral words and objective rhetorical strategies. Furthermore, rhetorical approaches are not about politics and people’s interests, so they are not political, at least in the ways that count as bad in the eyes of folks like Fulkerson and Hairston. Teaching rhetoric, he says, is more neutral, objective, because it isn’t teaching ideology.

Fulkerson then critiques Hairston by identifying the way she went about arguing, according to him, the correct side of the debate against CCS approaches to teaching writing. His argument is that she may have been right, but she didn’t exhibit a stance of neutrality, objectivity, and apoloticality, and that was “unfortunate”:

It was unfortunate that Hairston expressed her views so intemperately, liberally engaging in ad hominem argument and provoking the same from many respondents, and even more unfortunate that she later had to acknowledge seriously misquoting Cy Knoblauch, after identifying him as one CCS ideologue. Both features substantially reduce her ethos. She also described her own classroom approach in a vague way that made her seem an extreme expressivist, who would accept whatever her students said on primarily personal topics. (note 283)

Fulkerson’s discussion of Hairston’s argument is probably exactly what the WHST.9-10.1 anchor standard wants from students. Fulkerson focuses on the textual problems of Hairston’s argument, on her not staying strictly to the arguments at hand. She focused on other things, and became “intemperate” and not neutral and objective. He claims she was “engaging in ad hominem argument,” which could be another way of saying that she was paying attention to the people in the argument and not just their words. She had to acknowledge her own misquoting of a colleague and the resulting reduction of her own ethos in the debate. She offered a “vague” description of her own classroom, which looked like “extreme expressiv[ism]” (not good) that focused on “primarily personal topics,” that is, focused on students and their experiences instead of texts and words.

One way Fulkerson avoids politics in this debate is by avoiding discussing his own subject position – and all that that entails in languaging as a white, middle class man. In his analysis, he focuses on Hairston’s not using habits of white language well enough, although he describes it as not sticking to logos but he has a particular kind of logos in mind. She lost ethos, which interestingly is not something the anchor standard suggests is important in argument, yet ironically it’s vital in persuasion in a debate about the teaching of writing. If it were not important, he wouldn’t mention it.

But what about the racial and gendered politics in this debate? Could her unspoken subject position as a white woman, which Fulkerson would have known, shaded the way he understood the exchange and Hairston’s words? Does it seem reasonable to think that at that time (the mid-1980s), Hairston would be read as “intemperate,” that her passion, regardless of her logos-position, might be read as “intemperate”? Is it possible that the structures in schools and colleges and academic disciplines of the mid-1980s was such that it would be difficult for Hairston not to be read through her white woman-ness?

You might think that the differences Fulkerson mentions would include the politics of language. You might think it would include the raciolinguistic and gendered differences in languaging and the different orientations to the world inherent in different gendered, raced, and classed bodies in the world. You might think that Fulkerson means to include the differences in how a white woman from Michigan, who lives on a farm in Texas, who started as an instructor and moved up the ranks in the University of Texas to full professor and associate dean, as Hariston did, might reasonably have a different relation to words than her white male colleagues who also teach words. But these things are not a part of teaching argument in a middle class, whitely, and masculine fashion. We aren’t supposed to consider them, even as they implicitly affect our reading of others’ words. Ironic, right?

Fulkerson’s writing classroom is based almost solely on a rhetorical approach to teaching argument, an approach that presumes one kind of rhetoric, Western rhetoric – that’s his training. His textbook only offers this kind of rhetoric from Western sources. It’s the version of rhetoric that all those Pac-12 university writing directors were trained in, even as many struggle to free themselves from only that kind of rhetoric today. It’s the tradition that Graff and Birkenstein’s They Say/I Say templates come from. It’s likely the tradition you were trained in too as a teacher. Fulkerson also has concerns about paying too much attention to politics in writing classrooms, racial or otherwise, and focusing too much on the cultural aspects of language and people. It’s the arguments and how they are built that’s important to him. But focusing on just how something is built, avoids a number of ethical questions important to language classrooms. Who is served and who is harmed by building your arguments from solely white, Western, masculine sources?

Brave Work

Write for 15 minutes.

Make a list of the most important practices that define the center of your teaching. Try to list 6-8 practices. These practices could be how you respond to student writing in a particular way, some collaborative group work you tend to use, or a reading practice you engage students in, anything that defines your teaching practices.

Where did you get those practices? What books or authors, what mentors or past teachers, gave you these practices? How did you come to use them as your own? List these sources and identify each author, theorist, teacher, or mentor racially and gender-wise. Who has given you your pedagogy? What are the racial and gendered politics of it?

If politics is about power and people’s relations to power; if power is about the ways a system, like a society, a school, or an academic discipline, sets the environment so that rewards and opportunities move in particular ways to particular places and people; then focusing only on white, Western logos in classrooms is a way to maintain white, middle class, male hegemony. It’s one way to maintain the status quo. It is how white language supremacy is promoted without a single white supremacist in the room.

We all have some relation to what we write about, if we are successful, and especially if that writing is to be educational, an act of learning and growing. These relations are complicated and sometimes contradictory and beautiful and ugly and emotional and logical and everything in between. Good writing taps all of this, sifts it through its fingers. Good writing ain’t never been just about logic or evidence. But logic and evidence surely matters. It’s the how it matters and the why it matters that we have to continually figure out. This means that language learning in our classrooms is always an occurrence in the middle of messy, ambiguous people and places. It springs from our hearts, minds, and mouths. It invents and deconstructs us. It plays and wrestles. It makes and unmakes.

I’ve directed two different university writing programs, taught in six different universities and a community college. I’ve been the leader of my national organization for writing teachers (the Conference on College Composition and Communication, the largest conference under the National Council of Teachers of English -- the same organization that Hairston led). I’ve been an Associate Dean of Academic Affairs, Equity, and Inclusion for the fourth largest college in one of the largest universities in the U.S. I was a remedial English student in school too. I grew up in a mostly Black area of North Las Vegas, then a working class white area in Vegas. I was not allowed to be friends with any of the white kids in that white working class neighborhood because of my perceived race. I was seen as a “dirty Mexican.” There wasn’t an argument I could make that would ingratiate my neighbors to me. I was the definition of a “troublemaker,” of an untrustworthy person, one who was always under suspicion for doing something wrong. My words, no matter how I arranged them, were never effective. Logos wasn’t enough for me, and ironically, neither was it for my neighbors who used other things as well to judge me and my words.

This blog is offered for free in order to engage language and literacy teachers of all levels in antiracist work and dialogue. The hope is that it will help raise enough money to do more substantial and ongoing antiracist work by funding the Asao and Kelly Inoue Antiracist Teaching Endowment, housed at Oregon State University. Read more about the endowment on my endowment page. Please consider donating to the endowment. Thank you for your help and engagement.

Comments

Post a Comment